Conversing by Brush: A Partial P’iltam 筆談 Conversation between Robert van Gulik and Chŏng Inbo 鄭寅普 in the Collection of Leiden University Libraries

Introduction

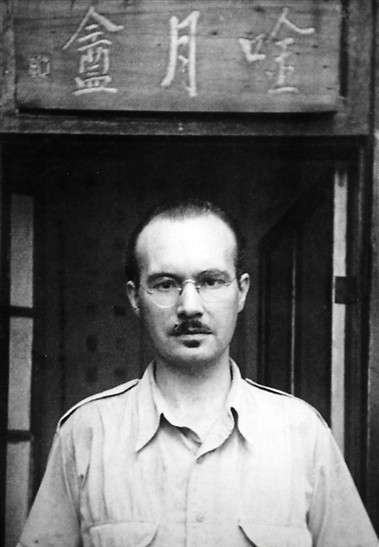

Legendary Dutch Sinologist, diplomat, and writer of international bestsellers Robert H. van Gulik (1910-1967)1 visited Korea a number of times during his service in Japan, both before and after the Pacific War.2 While stationed as a diplomat in Japan in the thirties, van Gulik had studied Korean according to his diaries.3 He also seems to have taken an interest in – presumably – classical Korean history and culture.4 After the war, van Gulik was appointed as political advisor to the ambassador to Japan – and to South Korea.5 In 1949, he made another trip to Seoul, formally as a private trip (“vakantietocht”), but, as he told his official Korean counterparts, in reality as a diplomat under orders from The Hague to scout out a possible location for the Dutch embassy in Seoul.6 At that moment, the Dutch diplomat responsible for South Korea was the Dutch ambassador stationed in Tokyo, which the Dutch embassy in Japan knew to be a potentially very sensitive point for Korea.7 The situation in Korea was deemed too unstable and dangerous for the Netherlands to establish a physical presence in Seoul.

1 We owe a debt of gratitude to: the van Gulik family for allowing us access to Robert van Gulik’s diaries; to Marc Gilbert, Leiden University Library reference librarian for Chinese, for making that access possible; to Kim Yongt’ae for his help in reading the manuscripts; to Vincent Chang for figuring out the identities of now rather obscure Republic of China diplomats; and to the Leiden University Library, in particular its Special Collections Department for providing us with digital copies of the van Gulik sources almost faster than the speed of light.

2 The Tongnip shinmun (Chongqing edition, 1943) limits its count to five actual visits made during his seven-year posting in Japan, whereas a set of South Korean newspapers published on 21 October 1949, including Chosŏn Ilbo, Chayu shinmun, and Hansŏng ilbo, drawing on a jointly conducted interview, reported—citing van Gulik’s own interview—that he had visited Korea “seven times” during the colonial period. The Tongnip shinmun reports that through several visits he developed a sustained interest in Korean affairs. On this basis, the newspaper further reports that van Gulik was invited by a Korean youth association to deliver a lecture. While this report does not in itself determine the location of the event, the wartime context, the fact that the Dutch were at war with Japan, van Gulik’s posting in Chongqing at the time, and the appearance of the report in the Chongqing edition together make it clear that the lecture was delivered in Chongqing rather than on the Korean peninsula. See Tongnip shinmun (Chongqing edition), June 1, 1943, “Han’guk Ch’ŏngnyŏnhoe tonch’ŏng Hwaran taesagwan pisŏ Ko Rap’ae-sshi yŏn’gang” [韓國靑年會敦請荷蘭大使館祕書高羅佩氏演講], Independence Hall of Korea, Korean Independence Movement Information System,

https://search.i815.or.kr/contents/newsPaper/detail.do?newsPaperId=DR194306010201; Chosŏn Ilbo, October 21, 1949, “Hwaran ŭi chin’gaek naehan” [和蘭의 珍客來韓], https://newslibrary.naver.com/viewer/index.naver?articleId=1949102100239102021&editNo=1&printCount=1&publishDate=1949-10-21&officeId=00023&pageNo=2&printNo=8141&publishType=00010 . The news of van Gulik’s visit was reported on the same day by five South Korean newspapers. Comparison of the texts shows that the content of the Hansŏng Ilbo is identical to that of the Chosŏn Ilbo, while the Chayu shinmun follows the same text with minor omissions; the Kyŏnghyang shinmun and Chayu minbo present increasingly condensed versions. Taking the Chosŏn iIbo article as a point of reference, this shared wording suggests that the reports were based either on a jointly held press conference on 20 October or on an article written by a Chosŏn ilbo reporter and subsequently circulated. In this paper, for terms that could be read according to either Chinese or Korean pronunciation, the latter is given.

3 In his diary, van Gulik jotted down the appointments he had – including those with his language teachers. It is not known who the person in the diary called Kim was, merely that he met van Gulik regularly and was paid for whatever service he rendered him. Given van Gulik’s own insistence that he had taken Korean lessons, and given the fact that “Kim” is a typically Korean family name, it seems reasonable to surmise that “Kim” was his Korean language teacher. The writers of his biography concur: see C.D. Barkman & H. de Vries-van der Hoeven, Dutch Mandarin: The Life and Work of Robert Hans van Gulik (Orchid Press: Bangkok, 2018), p. 48. Also see Leiden University Library, Robert Hans van Gulik archive, Or. 28.385: 3.63-64, on the following dates: June 13, June 23, June 27, June 30, September 29, October 3, October 6, October 10, October 13, October 17, October 21, October 27 (with the note “Kim paid for 8 times”), October 25, October 28, November 1, November 4, and November 8. Further lessons took place on November 10 (on which date is further said: “Kim paid for 4 [times]”), November 14, November 17, November 24, November 28, December 5 (when Kim had been “too late”), December 8, December 16, December 19, December 22 (after which he visited Hawley “with Kim” and dined together in “Prunier”), and December 26 (Kim was paid). Hawley refers to Frank Hawley (1901-1961), an English teacher in Japan and later special correspondent for The Times, who possessed a very large collection of books on Japan and China (approximately 16,000 volumes). Van Gulik wrote his obituary, “lest an outstanding scholar who greatly contributed to Japanese studies be forgotten through lack of documentary evidence.” See Leiden University Library, Robert Hans van Gulik archive, Or. 28.385: 56, on the following dates: February 16, March 2, May 11, May 22, May 29, June 8, June 15, and June 22. The meeting on June 12 was cancelled. Also see R.H. van Gulik, “In Memoriam: Frank Hawley (1906-1961),” in Monumenta Nipponica 16.3-4(1960): 214-227. In the following year, the pattern was continued with less frequency. In the months before his visit in October 1949 he noted in his diary every Korean class he took, but he did not specify who taught him. See Leiden University Library, Robert Hans van Gulik archive, Or. 28.385: 14.57 and later.

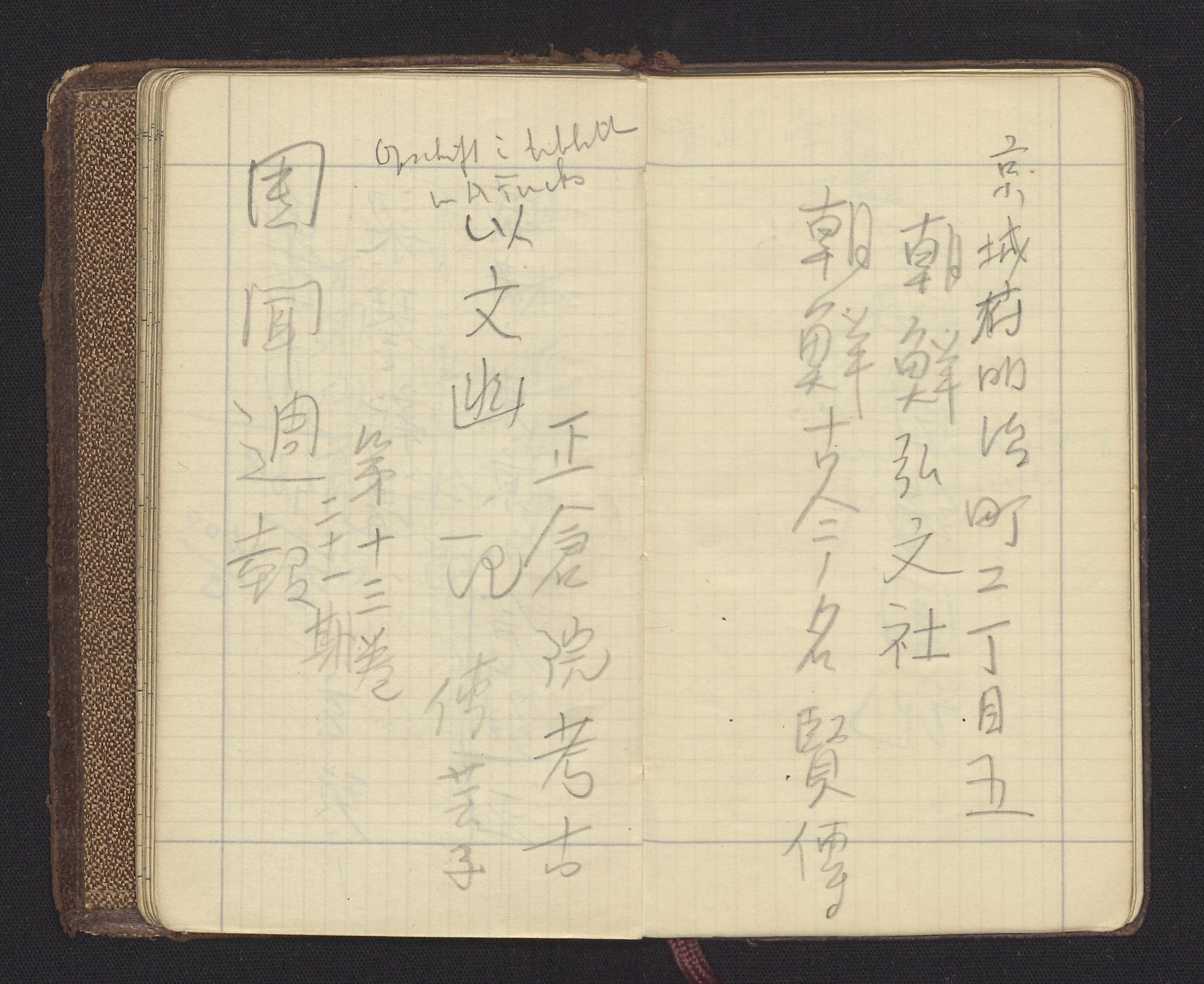

4 The earliest interest van Gulik expressed in Korea can be found in his diary for the year of 1937 (no further date). There, van Gulik had jotted down the name and address of a publisher in Keijō (present-day Seoul): Chōsen kōbunsha 朝鮮弘文社, as well as the name of a book, Chōsen kokon meikenden 朝鮮古今明賢傳 (Biographies of Korean sages, past and present). Copies of this book (published in 1923) can be found in the libraries of Tokyo Keizai University and Seoul National University.) The next page in the 1937 diary mentions the Seikyū gakusō 靑坵學叢, the quarterly journey of the Seikyū gakkai 靑坵學會 (Azure Hills Academic Association – Azure Hills is a historical designation of the Korean peninsula). The Seikyū gakkai had been established in 1930 at the Imperial University of Keijō (now Seoul) by Japanese historians working on Korean history. Later members would also include Korean intellectual giants such as Yi Nŭnghwa 李能和 (1869-1943). The association played an important role in the professionalisation and colonisation of the field of Korean history. The note in his otherwise conspicuously uncluttered diary seems to suggest that Van Gulik was a reader of the journal. See Leiden University Library, Robert Hans van Gulik archive, Or. 28.385: 3.63-64. Also see Cho Pŏmsŏng, “1930년대 靑丘學會의 설립과 활동.” 한국민족운동사연구, 107, 81-126.

5 The Netherlands had recognized the Republic of Korea just before van Gulik’s visit, on July 25, 1949, although full diplomatic relations only started from April 1, 1960.

6 See Karwin Cheung, “A portrait of the scholar as intelligence operative: Robert van Gulik in Seoul 1949,” in Provenance 5 (2024): 85-94. This is a good reconstruction of van Gulik’s visit, even though I wonder whether what Karwin Cheung describes as the duties of an intelligence operative, wasn’t part and parcel of the – admittedly less advertised but nonetheless expected - duties of the diplomat, especially in what was shaping to be the Cold War.

7 The report bears this out, as well as the appreciation from Syngman Rhee himself for the delicacy the Dutch diplomats showed here. See van Gulik, “Rapport,” p. 29.

8 Van Gulik stated in the report he wrote that he had told President Syngman Rhee that he had visited Korea many times after 1935, the year in which he had been sent to Tokyo as a diplomat. However, his diaries do not contain mentions of these visits. Since van Gulik wrote about his many visits in the context of his conversation with the president of South Korea, he may well have exaggerated his connection with Korea in that conversation in order to be polite, but his diaries contain preparations for a trip to Korea in the second half of the 1930s and he repeated this claim in the interviews he did in Korea. Also, his official report of the trip that landed on the desk of the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs supports this: he had been able to use the network he had built “during my pre-war visits to the country and during my stay in Chongqing.” Van Gulik had taken the trouble to learn spoken Korean, he seems to have ordered books by famous classical Korean intellectuals, and in the section meant for notes in his 1939 diary, he had written down the names of Korean dishes (such as kimch’iguk, kuk, t’ang, yakpap etc.) The authors of his biography also write that van Gulik had visited Korea several times while he was stationed in Japan in the thirties, but no source for this statement is given. See Barkman & de Vries-van der Hoeven, Dutch Mandarin p. 48; van Gulik, “Rapport van de politiek adviseur van de Nederlandse Missie in Japan over zijn dienstreis naar Korea, met geleidebrief,” Nationaal Archief. Inventaris van het archief van de Commandant Zeemacht in Nederlands-Indië, (1942-) 1945-1950, 2.13.72, Inventarisnummer 1441, p. 2; Leiden University Library, Robert Hans van Gulik archive, Or. 28.385: 14.76; Leiden University Library, Robert Hans van Gulik archive, Or. 28.385: 5.63-64.

9 Van Gulik had taken tens of conversation classes in Korean in the months before his 1949 trip to Seoul, but it seems he had already learnt a fair amount of Korean judging by the many lessons he had taken from a certain “Kim” while he had been stationed as a diplomat in Japan before war broke out. See note 3 for details.

Building on the network he had acquired during his previous trips and during his stay in the war in Chongqing, the Chinese nationalist capital,8 van Gulik was able to get mentioned in the Chayu shinmun, make an appearance on Korean radio, meet the president and high-ranking officials, and meet a number of leading Korean intellectuals, such as Chŏng Inbo 鄭寅普 and O Sech’ang 吳世昌. In preparation for these meetings (and perhaps also for a future ambassadorship to South Korea; van Gulik was appointed as ambassador plenipotentiary to South Korea in 1965 and would remain in that position until his death in 1967), van Gulik seems to have taken lessons in spoken Korean,9 but despite his fluency in Chinese and Japanese, obtaining fluency in Korean in a matter of months was not possible (even though he impressively read out aloud a speech on the Korean radio in Korean during his 1949 visit).

During the 1949 visit, van Gulik communicated by brush in Literary Sinitic with Korean cultural and intellectual giants such as the calligraphers An Chongwŏn 安鍾元 and O Sech’ang, and historian and public intellectual Chŏng Inbo. This structured these conversations along time-honored parameters, but conceivably would have led to a more restricted conversation. Yet, the genre of p’iltam 筆談, conversation in Literary Sinitic by brush, was a genre with a long, transnational history. P’iltam is a form of communication through written exchanges conducted when two parties did not share a spoken language but could both communicate by writing in Literary Sinitic, the classical lingua franca in East Asia.10

10 One of the earliest extant records of p’iltam is said to be an exchange conducted in 607 between envoys dispatched by Japan to the Sui dynasty and a Chinese Buddhist monk. This case demonstrates that, already by the early seventh century, written communication mediated by munŏn was being practically employed across East Asia. One of the principal objectives behind the dispatch of students from Greater Shilla, Parhae, and Japan to Tang China was likewise the training of civil officials proficient in the composition of diplomatic documents and refined prose. Given this institutional background, it is reasonable to assume that exchanges conducted through p’iltam were fairly frequent in Tang Chang’an, an international metropolis of the period.

This was not merely an auxiliary linguistic device; rather, it constituted a transnational mode of communication that emerged among intellectual communities sharing a common set of civilizational conventions. Heavy diplomatic traffic between states on the Korean peninsula and the Ming and Qing states in China, the Kamakura, Muromachi, Azuchi-Momoyama and Tokugawa states in Japan, and smaller entities such as Jurchen communities and Ryukyu meant that for centuries on end, there was ample opportunity for talented and quick-thinking scholars to engage in written exchanges in Literary Sinitic. Such exchanges often took the format of poetry and parallel prose. International reputations could be made in this way and there are records as far back as the Koryŏ period (918-1392) about Korean envoys who impressed their foreign hosts with the eloquence, wit, erudition, and insight displayed in p’iltam exchanges. Such exchanges were often recorded, in particular the celebrated ones, so they were well-known among later generations of scholars and diplomats.

It is from the seventeenth century onward that p’iltam begins to be preserved in especially rich documentary form. Practices of literati sociability and the evaluation of poetry and prose that had taken shape during the Ming dynasty were reconfigured within the new international order established after the founding of the Qing dynasty. Through tributary diplomacy with the Ming, Chosŏn had already internalized norms of diplomatic documentation and literary exchange centred on munŏn 文言, Literary Sinitic, and recognition by renowned Ming literati constituted an important cultural aspiration for Chosŏn intellectuals. These internalized norms continued to remain operative in Chosŏn’s engagements with Qing China and Japan, and the p’iltam by envoys to Qing China (such as those by Pak Chiwŏn 朴趾源) and those between Chosŏn envoys and Japanese scholars during Chosŏn embassies to Japan became celebrated examples of the international aspects of Sinitic learning.11 The viability of p’iltam as a method of international communication was predicated on the existence of a written cosmopolis in classical East Asia, so the decline and then the collapse of the classical way of performing international relations towards the end of the 19th century brought with it the disuse of p’iltam as a practical way of communication across language barriers. No longer was Literary Sinitic the lingua franca among diplomats and scholars alike. Entering the 20th century, p’iltam was rapidly becoming a stilted literary genre. Van Gulik and his counterparts in Korea, then, resurrected a historically well-attested genre by communicating through p’iltam. It should be mentioned here, by the way, that the Leiden University library only holds the responses van Gulik received from his counterparts. His own part in these brush conversations remained with their recipients in Korea. The p’iltam that will be examined in this article is not a simple written conversation, but a form of oral interaction that included handwritten calligraphy of the name of this study and poetic lines.

11 In the wake of the Imjin War, p’iltam and poetic exchanges (shi and mun compositions) were conducted most actively between Chosŏn literati and their Japanese counterparts, particularly in connection with the Chosŏn diplomatic missions (t’ongshinsa) dispatched to Japan. Within Japanese literati society of this period, receiving poetry from Chosŏn scholars or engaging in p’iltam with them even became something of a cultural vogue. Accordingly, in relations with Japan, Chosŏn was strongly conscious of displaying its status as the “civilized country of Chosŏn” through mun (文, literary cultivation). The scene depicted in Hanabusa Itchō’s 花房一朝 Bajō Kigō Zu 馬上揮毫圖, in which a mere page attending a mounted Chosŏn envoy writes characters on the spot for passersby along the roadside, symbolically illustrates both the popularity and the prestige of communication through writing. By communicating across borders in munŏn, the most authoritative written medium of the time, participants affirmed their belonging to a shared cultural–civilizational sphere. On this topic, see Kim Mun’gyŏng (Kim Munkyung), Chin Chaegyo (Jin Jaegyo), Ch’oe Wŏn’gyŏng (Choi Wonkyung,) et al., trans., Shipp’al segi Ilbon chishigin-dŭl, Chosŏn-ŭl yŏtpoda: P’yŏngurok 18세기 일본 지식인, 조선을 엿보다: 평우록 (Seoul: Sungkyunkwan University Press, 2013); and Chang Chinyŏp (Jhang Jinyoup), Chosŏn-gwa Ilbon, sot’ong-ŭl kkum kkuda 조선과 일본, 소통을 꿈꾸다 (Seoul: Minsogwŏn, 2022).

The scholar visits

Below are reproduced the excerpts from van Gulik’s diary that deal with his 1949 visit to Seoul. An English translation follows the Dutch. In the English translation, we have amended obvious mistakes and added to van Gulik’s Chinese transliteration of the names of the Koreans he met the appropriate Korean transliteration.12

12 Some of the names of Korean officials and others van Gulik met are given in a transliteration method appropriate to Korean. It is our assumption that the bearers of these names had devised a way to transliterate their names in Latin characters due to their knowledge of English or due to frequent contacts with (English-speaking) foreigners. In the absence of an established transcription, van Gulik resorted to the Wade-Giles method of transcribing Chinese.

Oktober 11, 1949 dinsdag

5 uur van huis, 7 uur in N. Western vliegtuig van Haneda vertrokken. In plane McNair ontmoet. 12 uur in Seoel aangekomen, late lunch alleen in Chosen hotel. 2 uur in taxi naar Pak, niet thuis, daarna naar Chün-shu-t’ang, waar boeken gezien en met Choi gepraat tot 4 uur. Via Hotel naar Amerikaansche ambassade, waar met Drumright, amb. Muccio, Stewart gesproken. 6 uur thuis, diner alleen. 8-9 Pak + vrouw en broer komen praten. 9.30 – 11 in bar gepraat met McNair, Angles An en Col. Frazer.

October 11, 1949, Tuesday

Left home at 5 o’clock, departed at 7 o’clock from Haneda in a N. Western airplane. Met McNair in the plane. Arrived in Seoul at 12 o’clock, late lunch alone in the Chosen Hotel. At 2 o’clock by taxi to Pak, not at home, then to Chün-shu-t’ang [Kunsŏdang13], where I looked at books and talked with Choi [Ch’oe Sŏnggi] until 4 o’clock. Via the hotel to the American Embassy, where I spoke with Drumright, Amb. Muccio, and Stewart.14 Home at 6 o’clock, dinner alone. 8–9 Pak + wife and brother15 come to talk. 9:30–11 talked in the bar with McNair,16 Angles An,17 and Col. Frazer.18

13 The Kunsŏdang 群書堂 was an antiquarian bookshop in central Seoul in the 1930s and 1940s which primarily dealt in books and documents written in Literary Sinitic. It was exceedingly popular among intellectuals, and it would have a monopoly on the distribution of some books by Chosŏn and Korean intellectuals, probably the books it published itself – it was also a publishing house. Its manager was Ch’oe Sŏnggi 崔成基, presumably the Mr Choi van Gulik mentions in his diary. The Kunsŏdang had a distinctly political flavor – it had published a book dedicated to Lyuh Woon-hyung (Yŏ Unhyŏng 呂運亨, 1886-1947), ultimately a Korean independence activist positioned to the left of the political centre who had proclaimed the People’s Republic of Korea on September 6, 1945. The PRK was declared illegal in the South by the American military government, while in the North it was incorporated into the DPRK.

14 John J. Muccio was the first ambassador to the ROK from 1949 to 1952. From 1948 to 1949 he had been Special Representative of the President in Seoul. Everett F. Drumright was Counsellor of the Embassy from 1948 to 1951. J. Stewart was Public Affairs Officer at the Embassy around this time. See Howard E. French, New York Times, May 22, 1989, http://www.nytimes.com/1989/05/22/obituaries/john-j-muccio-89-was-us-diplomat-in-several-countries.html.

15 This family is impossible to further identify in the absence of more information than their family name.

16 This may refer to Robert Wendell “Buck” McNair (1919-1971), a Canadian flying ace in WWII. He was stationed as an Air Advisor and Attaché of the Military Mission to the Canadian embassy in Japan in 1949 and fought as a fighter pilot in the Korean War. See Norman Franks, Buck McNair: The Story of Group Captain R W McNair DSO, DFC & 2 Bars, Ld'H, CdG, RCAF. Grub Street, 2001. I am not certain about this identification, but McNair’s status as diplomat in Japan and his documented action in the Korean War make him at least a viable candidate, even though Canada only established full diplomatic relations with South Korea and opened an embassy in 1963. Alternatively this refers to an otherwise unknown R.P. McNair, for on an otherwise empty page at the back of van Gulik’s diary for 1949, we find the following note: “R.P. McNair, 812 Rose Lane, Falls Church, Va.” See Leiden University Library, Robert Hans van Gulik archive, Or. 28.385: 14.97.

17 I have not been able to decipher this name. The family name of “An” seems clear, but the preceding name is not – given the fact that here the Korean or Chinese family name comes last, while van Gulik elsewhere always respects the original East-Asian order of family name – personal name, this name probably refers to someone who lived in the United States or Europe for a significant period. It remains a matter of speculation, however, whether van Gulik’s handwriting here can be deciphered as reading “Angles An” or whether another reading should be preferred.

18 “Frazer” refers to Colonel J.W. Fraser, who served as US Military Attaché in 1949. In his report, van Gulik also misspells his name as “Frazer”; van Gulik, “Rapport,” p. 24. Bruce Cumings’ The Origins of the Korean War refers to some of Fraser’s activities. See Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, Part 2, p. 828n.59: “895.00 file, box 7127, Embassy to State, March 25, 1949» transmitting a report on the guerrillas by Col. J. W. Fraser.” After the war Fraser was described as a former military attaché: see Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, Part 2, p. 814n.77: “Liem and Col. J. W. Fraser, a former military attaché in Seoul, sought again to utilize Jaisohn’s services, this time in a propaganda and public affairs capacity. See 795.00 file, box 4267, Fraser to Weckerling, July 26, 1950, attached to 795.00/8-250.”

Oktober 12

9 uur met boekhandelaar Choi naar moderne boekwinkel, waar boeken gekocht, en daarna met hem naar tentoonstelling in National Library. 10.30 jonge Pak19 komt, met hem gepraat, 12 uur oude Pak komt, met hun geluncht, daarna samen naar oude geleerde An Chung-yüan gewandeld, waar gepraat. 4 uur in hotel in jacquet verkleed, en naar Min. B.Z., waar gesproken met Min. Lin, vice-Minister Cho, en Min. v. Ed. An Ho-sang. 6-7 Kim Man-soo komt over paspoort spreken.

19 I have not been able to identify either young Pak or old Pak.

October 12

At 9 o’clock went with the bookseller Choi to a modern bookshop. Bought books there, and afterward went with him to an exhibition in the National Library. At 10:30 young Pak arrives, talked with him; at 12 o’clock old Pak arrives, lunched with them, then together walked to the old scholar An Chung-yüan [An Chongwŏn20], where we talked. At 4 o’clock changed into a morning coat in the hotel, and went to Min. of Foreign Affairs. There I spoke with Min. Lin,21 Vice-Minister Cho,22 and Min. of Ed. An Ho-sang.23 6–7 Kim Man-soo24 comes to talk about passport.

20 An Chongwŏn 安鍾元 (1874-1951) was one of the foremost calligraphers of colonial Korea – in South Korea, he was one of the jury members of the annual national calligraphy competition. Given van Gulik’s passion for calligraphy, he was an obvious person to meet. An was 77 years old when van Gulik met him.

21 Presumably, Im Pyŏngjik 林炳稷 – Lin is the Chinese reading of the Korean Im-, Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1949 and 1951. Im was a confidant of President Yi Sŭngman, with whom he had spent 36 years in exile in the United States.

22 Cho Chŏnghwan, the Fourth Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1956 and 1959, who had previously served as Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1949 and 1951.

23 An Hosang was the first Minister of Education of the ROK and a faithful adherent of the kind of pseudo-historical theories that claim a truly grandiose past for the Korean nation. In his long interview with Dutch journalist Hans Olink in 1999, George Blake reminisced that An had a portrait of Hitler in his office. See Hans Olink, “George Blake, meesterspion.” An was known for his explicit fascist sympathies before the liberation of Korea and his “One-People Principle” smacks of Nazism. He was also the founder of an extreme-right student corps, the Taehan Youth Corps (Taehan Ch’ŏngnyŏndan 大韓靑年團), which – somewhat improbably –boasted of having a membership of around two million members. For a description of An’s study abroad in Germany in the 1920s and his contacts with German fascists, see Frank Hoffmann’s impressively researched monograph-length article: Frank Hoffmann, “Berlin Koreans and Pictured Koreans,” in Koreans and Central Europeans: Informal Contacts up to 1950, Vol. 1 edited by Andreas Schirmer (Vienna: Praesens, 2015). Pp.. xi, 241 pp. ISBN: 9783706908733 (paper, also available as e-book). It is altogether credible that Blake saw a portrait of Hitler in An’s office.

24 I find it impossible to determine who Kim Man-soo (Kim Mansu) was. I have found two persons with that name that were active in 1949, but both in Chŏlla-do Province, one as a policeman, the other as the regional branch manager of a bank in Mokp’o. Neither seems a logical candidate for the Kim Mansu van Gulik met.

Oktober 13

9 uur naar Mungyobu, met Minister An Ho-sang gesproken, daarna naar National Museum, Kim Che-wen niet getroffen. Naar Am. ambassade, McNair, Lt. Fairchild gesproken. Lunch alleen in hotel. Na lunch half uur op kamer gerust. Naar Chin. ambassade, Shao Yü-lin ziek, 3de secretaris Chen Heng-li gesproken. Rond gewandeld, antiquair Kim binnengelopen, waar Ri ontmoet. Naar Am. ambassade, waar gesproken met McNair, Frazer en Stewart. 4-5 gepraat bij Kol. David, Nat. Police H.Q. 5 uur sandwich in bar en op kamer gerust. 6-7 Kim Che-wen + vrouw komen praten. 7 uur naar huis Drumright, waar buffet-dinner met Amb. Shao, counsel Hsü, Min. Holt, Min. Yung, Secr. Gen. Ch’ŏn + vrouw, Steward, e.a.

October 13

At 9 o’clock to the Mun’gyobu [Ministry of Education], spoke with Minister An Ho-sang, then to the National Museum, did not meet Kim Che-wen [Kim Chaewŏn25]. Went to the American Embassy, spoke with McNair and Lt. Fairchild.26 Lunch alone in hotel. Rested half an hour in room after lunch. To the Chinese Embassy, Shao Yü-lin ill,27 spoke with 3rd secretary Chen Heng-li.28 Walked around, dropped by at antiquary Kim,29 where I met Ri.30 Visited the American Embassy, where I spoke with McNair,31 Frazer, and Stewart. 4–5 talked with Col. David32 at the National Police H.Q. At 5 o’clock a sandwich in the bar and rested in room. 6–7 Kim Che-wen + wife come to talk. At 7 to Drumright’s house, where buffet dinner with Amb. Shao, counsel Hsü,33 Min. Holt,34 Min. Yung,35 Secr. Gen. Ch’ŏn36 + wife, Steward, and others.

25 Kim Chaewŏn (1909-1990), generally seen as the founding father of modern South Korean archeology and the first director of the National Museum of Korea. He was a towering figure in postwar cultural and academic circles.

26 Ik heb Lt. Fairchild niet kunnen identificeren.

27 Shao Yulin 邵毓麟 (1909-1984) was the first ambassador of the Republic of China to South Korea, representing the Nationalist Party. Charles Kraus has written an interesting footnote on Shao in: Charles Kraus, “Bridging East Asia's Revolutions: The Overseas Chinese in North Korea, 1945-1950,” Journal of Northeast Asian History 11.2 (2014): 37-70. Shao wrote a book on his period in South Korea, his memoirs as ambassador: Shao Yulin, Shi Han huiyilu : Jindai Zhong Han guanxi shihua 使 韩 回忆录 : 近代 中 韩 关系 史话 (Taibei 台北: Zhuanji wenxue chubanshe 传记文学出版社, 1980).

28 Thanks to Vincent Chang, Cheng Heng-li can be identified. He is mentioned in Shao’s memoirs om p. 111. He was Third Secretary and Vice-Consul Ch’en Heng-li 三等祕書兼副領事 陳蘅力 (Hanyu Pinyin: Chen Hengli). For more details, see https://gpost.lib.nccu.edu.tw/view_career.php?name=陳衡力. It should be noted that this government source uses the character 衡 for “heng” instead of the character Shao uses: 蘅 .

29 Perhaps this was Kim Chŏnghwan 김정환, the founder and owner of the Tongin kage, a famous historic art gallery and antique shop, founded in 1924 in Seoul. In 1949 it was still located in Tongin-dong. It later relocated to Insa-dong, where it still exists to this day.

30 It is impossible to establish the identity of “Ri” only on the basis of his (her?) family name.

31 This may either mean that McNair was an American whom I cannot identify, or that the Canadian diplomat McNair (cf. note 16) either also visited the American embassy like van Gulik, or, what seems more plausible given the context, perhaps had an office there as an ally of the United States.

32 I have not been able to identify Colonel David. The South Korean police had become independent with the establishment of the Republic of Korea, but it still used American advisors and had largely retained its colonial structure and employees. Its reputation was extremely bad for the violence and torture it was associated with. It should not be forgotten that when van Gulik was in Seoul, not only was the political situation extremely unstable and was travel outside of Seoul potentially dangerous due to the activities of Communist guerrillas, but the Jeju Uprising had only just been quashed – during which tens of thousands of people had been killed, among others by members of the national police. The national police in 1949 in other words was the kind of police force one expected in a dictatorship. For a more detailed overview of the early years of the Korean police see Jeremy Kuzmarov’s article (which is useful, but has some weak points in that it was not written by someone with extensive Korean Studies training): Jeremy Kuzmarov, “Police Training, ‘Nation-Building,’ and Political Repression in Postcolonial South Korea,” The Asia-Pacific Journal 10: 27.3 (2012).

33 It almost proved impossible to establish the identity of “Counsel Hsü” only on the basis of his family name and diplomatic rank, but again Vincent Chang came to the rescue. Counsellor and Vice-Consul Hsu Shao-ch’ang 參事兼總領事 許紹昌 (Hanyu Pinyin: Xu Shaochang) appears in a group photo in Shao’s memoirs. For more details, see https://gpost.lib.nccu.edu.tw/view_career.php?name=許紹昌.

34 Captain Sir Vyvyan Holt (1896-1960) had been appointed British Consul-General to South Korea in 1948 and Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary in 1949. He was taken prisoner by the North Koreans in 1950 and spent three years in captivity, like Holt. The infamous Soviet spy George Blake (1922-2020) was one of his subordinates and was turned during his captivity.

35 I wonder whether “Min. Yung” might be Yun Posŏn 尹潽善 (1897-1990), who served as Minister of Commerce and Industry between 1948 and 1950. Yun briefly served as South Korea’s second president between 1960 and 1962 and as the only president of South Korea’s Second Republic.

36 I have not been able to identify this person.

Oktober 14

Aan ontbijt kennis gemaakt met Kodaki, daarna naar Britsche Legatie gewandeld, Blake, Faithful en Holt gesproken. via Jung-Ch’ang boekhandel naar hotel terug gewandeld. 12-3 Col. Frazer en McNair komen lunchen in hotel, daarna samen naar P. Ex. Daarna naar antiquair Kim, shêng gehaald. In hotel brief voor E geschreven, daarna op kamer gerust. 6.30 in taxi naar huis Dr. Kim achter Museum, waar Koreaansch diner, en na diner met mounter Kwak gepraat.

October 14

Made acquaintance with Kodaki37 at breakfast, afterwards walked to British Legation, spoke with Blake,38 Faithful,39 and Holt. Walked back to the hotel via Jung-Ch’ang bookshop.40 12–3 Col. Frazer and McNair come to lunch in the hotel, afterward together to PX. Then to antiquary Kim, fetched a shêng.41 Wrote a letter for E42 in hotel, then rested in room. At 6:30 by taxi to the house of Dr. Kim behind the Museum, where we had a Korean dinner, and after dinner talked with the mounter Kwak.43

37 I have not been able to identify this person.

38 George Blake (1922-2020), the famous mole in the British Secret Intelligence Services, who became a communist during his three-year captivity in North Korea. He was sent to Seoul in his capacity as intelligence officer of the SIS. After returning to Great Brittain in 1953, he spied for the Soviet Union until his capture in 1961. Sentenced to 42 years in prison, he escaped in 1966 and fled to Moscow, where he stayed until his death in 2020. Born and raised in Rotterdam to an Egyptian-British father and Dutch mother, he spoke Dutch as his native language. See George Blake, No Other Choice (Simon & Schuster, 1990); Simon Kuper, Spies, Lies, and Exile: The Extraordinary Story of Russian Double Agent George Blake (The New Press, 2021); E.H. Cookridge, The Many Sides of George Blake, Esq.; the Complete Dossier (Vertex Books, 1970).

39 Faithful was the Counsellor at the British Legation. Alternatively, again according to Blake, he was the first secretary. See Blake, No Other Choice, p. 5.

40 I have not been able to find information on this bookshop.

41 A shēng is a traditional Chinese instrument. It consists of several pipes and is mouth-blown.

42 Teruyama Etsuko, often mentioned in the diaries as “E”, a good friend in Japan of van Gulik. See Barkman & de Vries-van der Hoeven, Dutch Mandarin, pp. 174, 184-85, 281-82.

43 Mounter Kwak will unfortunately remain unidentified. Van Gulik’s diary includes a reference to a certain Kwak Kiun 郭紀云 (if one reads the name according to Korean pronunciation), but this person seems to refer to the Chinese scholar Zhang Chunyi (1871-1955).

Oktober 15

9 uur Rechter Pak + vriend Pak komen praten tot 10 uur, daarna met Pak naar boekhandelaar, en samen naar Fransch consulaat gewandeld. Daar tot 12.30 met Costello bier gedronken, en 1.20 Costello brengt mij in jeep terug naar hotel. Alleen lunch, daarna gerust. 2.30 Kim Man-soo komt over paspoort praten. 4 uur Dr. Kim komt met journalist Cheng, samen naar huis van den yangban Cheng, waar op papier geconverseerd over luit en mounting. 6-7 Rechter Pak + Pak komen in hotel, over geld gesproken. 7 uur in jeep Fransch consulaat naar Castilhes, waar diner met Martel en Monseigneur. 鄭寅普,薝園山房.

October 15

At 9 o’clock Judge Pak + friend Pak come to talk until 10 o’clock, afterwards with Pak to the bookseller, and together walked to the French consulate. There I drank beer with Costello44 until 12:30, and at 1:20 Costello brings me back to the hotel in a jeep. Lunch alone, then rested. 2:30 Kim Man-soo comes to talk about the passport. At 4 o’clock Dr. Kim comes with the journalist Cheng,45 together to the house of the yangban Cheng,46 where we conversed on paper about the lute and mounting. 6–7 Judge Pak + Pak come to the hotel, spoke about money. At 7 o’clock in a jeep to the French consulate to Castilhes, where I had dinner with Martel47 and Monseigneur.48 鄭寅普,薝園山房.49

44 This seems to refer to William “Bill” Costello (1904-1969), a journalist who served as the Far East News Director of CBS in Tokyo from 1946 to 1951.

45 I do not know who this is.

46 Chŏng Inbo 鄭寅普 (1893-1950) was one of colonial Korea’s most influential intellectuals, independence activists, and historians. A proponent of the Chosŏnhak (Korean Studies) movement, Chŏng was an indefatigable advocate of traditional Korean culture and of Korea’s history, a proper awareness of which he thought would be the key to Korean independence. He spent significant time in China in exile engaged in independence activities, with the likes of Shin Ch’aeho and Pak Ŭnshik, published articles, books, and newspaper articles, and wrote the epitaph for ex-Emperor Sunjong’s tomb when he died in 1926. He was kidnapped to the north in 1950 with the outbreak of the Korean War and is presumed to have been killed there in November of the same year. See the chapter on Chŏng in Cho Tonggŏl 조동걸, Han Yongu 한영우 & Pak Ch’ansŭng 박찬승, Han’gug-ŭi yŏksaga-wa yŏksahak 한국의 역사가와 역사학, vol. 2 (Ch’angbi 창비, 1994), pp. 172-181.

47 Martel, the French Vice-Consul, who lived in Seoul together with his aged mother and sister. See Blake, No Other Choice, p. 128, 136.

48 Presumably one of the religious officeholders van Gulik met while in Seoul.

49 These are the Chinese characters for “Chŏng Inbo” and for “Tamwŏn”, his literary pseudonym, followed by “sanbang,” which means something like “mountain retreat” and is perhaps a reference to Chŏng’s mountain retreat.

Oktober 16

Na ontbijt naar antiquair Kim, shêng betaald. Daarna naar Choi en boekhandel, met hem naar huis, en gepraat tot 12 uur. Terug naar hotel. Dr. Kim komt, samen in hotel geluncht, dan naar boekhandel gewandeld, en bezoek gebracht bij Wu Shih-ch’ang 吴世昌. Via Pagoda Park naar huis, in hotel bier en sandwiches, daarna Chineesch diner in Ga-jo-en. ’s Avonds op kamer boeken doorgekeken.

October 16

After breakfast to antiquary Kim, paid for the shêng. Then to Choi and the bookshop, with him to his house, and talked until 12 o’clock. Back to the hotel. Dr. Kim comes, lunched together in the hotel, then walked to the bookshop, and visited Wu Shih-ch’ang 吳世昌 [O Sech’ang].50 Via Pagoda Park51 back home, in hotel beer and sandwiches, then Chinese dinner in Ga-jo-en.52 In the evening looked through books in the room.

50 Born into a wealthy family of interpreters, O Sech’ang (1864-1953) was a painter, calligrapher, progressive politician and independence activist. He was involved in progressive politics before the turn of the century, fleeing the country to Japan several times to avoid prosecution. He was one of the leaders of the March First-movement in 1919, a signee of its declaration, and an influential leader in the field of cultural and artistic production. When van Gulik met him, he was already 85 years old, but still a very respected figure at the right of the political spectrum.

51 The park in Central Seoul where the Declaration of Independence had been read on March 1, 1919.

52 This seems to be the Japanese reading of Asawŏn (雅叙園), a Chinese restaurant popular with van Gulik and other foreigners. He calls it “Asawŏn” in his notes for October 20 below (see there for more information on this restaurant). Asawŏn predates, by the way, the famous Japanese hotel and restaurant with the same name: Gajoen in Tokyo. Asawŏn was founded in 1907, Gajoen in 1931. The presence of a famous hotel/restaurant with the same name in Tokyo may have led van Gulik to referring to the restaurant in Seoul both as Ga-jo-en and Asawŏn.

Oktober 17 Maandag

9 uur ontbijt, daarna boeken ingepakt. 10 uur naar Am. ambassade, met Drumright, Henderson en Col. Frazer gesproken, en S.F. in Tokyo opgebeld. Maag medicijn in dispensary gehaald. 1-3 lunch bij ambass. Muccio, met Drumright. Alleen naar boekhandels in Chong-no gewandeld, 5 uur thuis omgekleed.

5.30 Kim Man-soo komt met vrouw in hotel, geeft kiseng dinner in Koreaansch restaurant Ch’ing-hiang-yüan. ’s Avonds 9 uur thuis, boeken uitgezocht.

October 17 (Monday)

9 o’clock breakfast, then packed books. At 10 o’clock to the American Embassy, spoke with Drumright, Henderson,53 and Col. Frazer, and phoned S.F. in Tokyo. Got stomach medicine at the dispensary. 1–3 lunch at Ambassador Muccio’s, with Drumright. Walked alone to the bookshops in Chong-no, at 5 o’clock home to change.

5:30 Kim Man-soo comes to hotel with wife, gives a kisaeng dinner in the Korean restaurant Ch’ing-hiang-yüan [Ch’ŏnhyangwŏn].54 Home at 9 in the evening, sorted books.

53 Gregory Henderson (1922-1988), US diplomat and influential Korea expert. Author of the classic study of South Korean politics: Korea: The Politics of the Vortex (Harvard University Press, 1968).

54 Ch’ŏnhyangwŏn (天香園, or Tenkō’en in Japanese) was one of the three most famous traditional Korean restaurants in Seoul during and right after the colonial period. See Katarzyna J. Cwiertka, Cuisine, Colonialism and Cold War: food in twentieth-century Korea (London: Reaktion Books, 2013) <doi:10.5040/9781780230733>.

Oktober 18

9.30 naar museum, met Dr. Kim naar plechtigheid in Confucius tempel. Daarna naar Koreaansche dokter met Duitsche vrouw, en naar Seoul Universiteit, waar Chin. prof. Kim ontmoet. Lunch met Dr. Kim in hotel, daarna naar museum, met Li naar A-Lakpu, en naar antiquairs. 5 uur in hotel, waar G. Henderson mij komt halen, thee bij hem thuis. 7 uur naar ga jo en, waar diner van ambassadeur Shao, met Drumright, beide Costello’s, Koreaan Li Chung-hwang, en leden Chin. ambassade. 9.30 thuis.

October 18

9:30 to the museum, with Dr. Kim to the ceremony in the Confucius temple.55 Then to a Korean doctor with a German woman,56 and to Seoul [National] University,57 where we met the Chinese prof. Kim.58 Lunch with Dr. Kim in the hotel, then to the museum, with Li59 to A-Lakpu,60 and to antiquaries. 5 o’clock back in the hotel, where G. Henderson comes to fetch me, tea at his home. At 7 to Ga-jo-en, where dinner of Ambassador Shao, with Drumright, both Costellos, the Korean Li Chung-hwang,61 and members of the Chinese Embassy. Home at 9:30.

55 The ritual that is referred to here was for the birthday of Confucius. In 1949, October 18 corresponds with the 27th day of the eighth month, which traditionally has been regarded as Confucius’ birthday. The term “Confucius temple” may be understood as referring to the Sungkyunkwan Munmyo 文廟, the officially recognized shrine for the veneration of Confucius in Seoul. The principal ritual traditionally performed at the Munmyo was the Sŏkchŏn 釋奠 ritual, a Confucian state ritual honoring Confucius and other major sages. Sŏkchŏn was conventionally conducted twice a year, in spring and autumn, on the first chŏng (丁) day of the second and eighth lunar months. From 1937, during the Japanese colonial period, the dates of the rite were altered to fixed solar dates—15 April and 15 October. Following liberation, and in conjunction with the reorganization of the Munmyo pantheon in 1949, during which Korean Confucian worthies were relocated to the main shrine hall, the traditional spring and autumn Sŏkchŏn were suspended, and a commemorative Sŏkchŏn was instead performed on Confucius’s birthday. Eventually Sŏkchŏn was again performed on the traditional lunar dates. Korean Sŏkchŏn is regarded as having preserved the original form of ancient Confucian ritual with unusual fidelity, including the performance of classical ritual music. See Sungkyunkwan, http://www.skk.or.kr/, and the Korea Heritage Service.

56 Too little information to determine who these persons were.

57 South Korea’s leading university, the post-colonial reincarnation of Keijō teikoku daigaku, then still located at Taehangno 大學路.

58 I wonder whether this could be Kim Kugyŏng 金九經 (1899-1950), a then famous pioneer in the study of the historical relations between China, Japan, and Korea, in the study of Chinese and Buddhist philosophy, and someone with excellent networks as well as research and teaching experience in all three countries. He taught the famous Chinese linguist and educator Wei Jiangong 魏建功 (1901–1980) Korean, had studied under the grand man of Japanese sinology Naitō Konan (內藤湖南, 1866-1934) and legendary Buddhist scholar Suzuki Daitetsu (鈴木大拙, 1870-1966), leading Suzuki to ask Kim for his critical view on his work on Sŏn/Zen. His publications on Manchu texts and on Buddhism, in particular his pioneering correction and collation of partial manuscripts, were very influential. After the liberation, he returned to Korea and become one of the first professors at the Department of Chinese Literature at Seoul National University. Van Gulik may have met him during his period in Japan or during his frequent visits to Beijing and will probably have known of him and his work. Kim disappeared in 1950 when the North Korean army took over Seoul. His activities in Japan during the colonial period and his close collaboration with Japanese scholars have given him the reputation of having been pro-Japanese, which has led to his present-day obscurity. See Yi Yongbŏm, “Sŏul-dae Chungmun’gwa ch’odae kyosu, Kim Kugyŏng 서울대 중문과 초대(初代)교수, 김구경,” Wŏn’gwang-dae Hanjungil kwan’gye pŭrip’ing 원광대 한중관계브리핑. February 7, 2022 https://kcri.wku.ac.kr/?p=6185. Accessed on December 14, 2025; also see Kim Cheonhak, “Kim Kugyŏng’s Liminal Life: Between Nationalism and Scholarship,” in New Perspectives in Modern Korean Buddhism: Institution, Gender, and Secular Society (State University of New York Press, 2022), edited by H.I. Kim & J.Y. Park, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781438491332.

59 It is impossible to identify this person merely on the basis of a (very popular) family name.

60 This was the successor to the Yiwangjik aakpu 李王職雅樂部, the Chosŏn Royal Institute of Music. This was a colonial institution that dealt with the affairs of the royal family after the annexation by Japan. The musicians who had performed court music at the Chosŏn court were more or less organically transferred to this institution, which in order to remain relevant and survive in a world where there was no longer a ruling royal family, changed itself into a teaching institution. When in 1945 the Yiwangjik (Institute of Royal Affairs) was dissolved, the Aakpu survived as the Kuwanggung aakbu 舊王宮雅樂部 (Old Royal Court Music Institute), the forerunner of what would eventually become the Kungnip kugagwŏn 國立國樂院 (National Gugak Centre). It goes without saying that van Gulik would have been extremely interested in such an institute and its musicians.

61 I have not been able to determine who Li Chung-hwang was.

Oktober 19

9 uur 6 pakken Koreaansche boeken naar Tokyo gestuurd. 10 uur bij antiquair Kim om koopen Buddha gepraat. 11-12 in hotel gerust, en verkleed. 12-1 met journalist Tei geluncht, 1.30-2 bezoek gebracht bij de President. Daarna naar museum gewandeld, met Dr. Kim en journalist + schilder naar Cheng Yin-pu, waar calligraphie; in hotel allen samen bier en sandwiches. 6 uur Pak van de rechter komt in hotel afspraak YMCA maken. 7 uur naar Britsche Legatie, waar diner met Ch. Hunt, 2 Danes, en Stewards (ECA) en Drew.

October 19

At 9 o’clock sent 6 parcels of Korean books to Tokyo. 10 o’clock at antiquary Kim talked about buying Buddha. 11–12 rested in the hotel and changed. 12–1 lunched with the journalist Tei,62 1:30–2 paid a visit to the President. Afterwards walked to the museum, with Dr. Kim and the journalist + painter to Cheng Yin-pu [Chŏng Inbo], where calligraphy; in the hotel all together beer and sandwiches. At 6 o’clock Pak the judge comes to the hotel to arrange appointment at the YMCA. At 7 to the British Legation and dinner with Ch. Hunt,63 2 Danes, and the Stewards (ECA)64 and Drew.65

62 I do not know who this person is, but “Tei” may simply be the Japanese reading of the Korean family name “Chŏng.” Van Gulik wrote about meeting a journalist called Chŏng earlier in his diary, so this would be a reasonable assumption. Unfortunately, this does not get us anything closer to the identity of this person.

63 Father Charles Hunt (1889-1950), an Anglican missionary in Seoul who was sent by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (S. P. G.). He arrived in Korea in 1915, served during WWII in the British navy as chaplain and returned to Korea in 1946. He was taken captive by the North Korea army in 1950 and taken north. There he died during a particularly gruesome nine-day march (“Death March”) of over 80 kilometers which claimed the lives of 500 out of 800 prisoners. See Brother Anthony, “Charles Hunt: Missionary and Martyr,” in Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Korea Branch, 96 (2023):23-36.

64 Economic Cooperation Administration, a US office through which Marshall Plan help was implemented in South Korea.

65 I have not been able to identify this person.

Oktober 20

10 uur Pak komt, samen naar YMCA, waar Mr. Hyon gesproken. Daarna samen naar Tung-wu-kuan, waar boeken gekocht. 12 uur Drumright, Frazer en Henderson komen in hotel + Dr. Kim, ik geef hun lunch in Asawen. Daarna met Dr. Kim naar mounter, aanteekeningen gemaakt, en Min. v. B.Z. waar exit-permit, en met Min. Lin, Huang en Dr. Kim science tentoonstelling in museum gezien. 5 uur in hotel terug. 6 uur Kim Man-soo komt, samen met Kon naar huis Pak van Hwa-hsin, waar Koreaansch diner. 8.30 thuis. Vroeg naar bed.

October 20

10 o’clock Pak comes, together to the YMCA, spoke with Mr. Hyon.66 Then together to Tung-wu-kuan,67 bought books. At 12 Drumright, Frazer, and Henderson come to the hotel + Dr. Kim, I give them lunch in Asawen.68 Afterwards with Dr. Kim to the mounter, took notes, and to the Foreign Affairs Min., received exit permit, and with Min. Lin, Huang,69 and Dr. Kim to the science exhibition in the museum. 5 o’clock back in the hotel. 6 o’clock Kim Man-soo comes, together with Kon70 to the house of Pak of Hwa-hsin [Hwashin],71 Korean dinner there. Home 8:30. Early to bed.

66 Mr Hyon was Hyŏn Tongwan 玄東完 (D.W. Hyun, 1899-1963), who was connected to the YMCA almost from birth to death. He was a basketball player for the YMCA’s famous colonial period sports team, later a coach, then moved on into YMCA management. He was appointed general secretary of the YMCA in 1948 and founder of the YMCA’s Boy’s Town in Seoul, which took care of war orphans.

67 Is this a corrupted transliteration of T’ongmungwan 通文館, the famous antiquarian book shop in Insa-dong? But the transcription is not correct in that case. Still, this would be a book shop van Gulik would go to.

68 Chinese restaurant founded in 1907. Asawŏn (full name: Chunghwa yorijŏm Asawŏn 中華料理店 雅叙園), which closed its doors in 1970, was a large and popular restaurant, with four stories that could hold over 900 guests, which after liberation was sought out by the American army and other foreigners. The restaurant also drew a clientèle of predominantly right-wing politicians, and from the sixties onwards, successful entrepreneurs as well.

69 Perhaps this refers to the previously unidentified Li Chung-hwang.

70 I have no idea who this might be.

71 Hwashin Department Store (Hwashin paekhwajŏm 和信百貨店)) was a famous department store dating from the colonial period, when it was the only Korean-run department store. It closed its doors in 1987. In its place Chongno Tower now stands.

Oktober 21

9 uur Kim en 2 Pak’s komen, allen samen naar Hwa-hsin. Daarna met beide Pak’s naar Mr. An, waar calligraphie. 11.30 in hotel terug, naar antiquair Kim waar Buddha gehaald, en bij Airways afgeleverd, waar tevens passage betaald. 12 uur Dr. Kim, daarna journalist Cheng komen in hotel, lunch met Dr. Kim, 2 uur samen naar thee-partij van Min. Min. 4.30 met Dr. Kim naar Radio station, waar speech gehouden. 5 uur in hotel, beide Pak’s komen, samen naar huis jonge Pak, waar diner met rechters en Dr. Liang. 9 uur in hotel terug, waar Kim Man-soo en vrienden komen. Verder bagage gepakt.

October 21

9 o’clock Kim and 2 Paks come, all together to Hwa-hsin. Afterwards with both Paks to Mr. An, did some calligraphy there. 11:30 back in hotel, to antiquary Kim where fetched the Buddha, and delivered it at Airways, where passage also paid. 12 o’clock Dr. Kim, then journalist Cheng comes to the hotel, lunch with Dr. Kim, at 2 o’clock together to the tea party of Min. Min.72 4:30 with Dr. Kim to the radio station and gave a speech. 5 o’clock back in the hotel, both Paks come, together to the house of young Pak, where dinner with judges and Dr. Liang.73 9 o’clock back in the hotel, where Kim Man-soo and friends come. Packed further luggage.

72 I wonder whether “Min” is a misspelling of “Lin”, which would then refer to Minister of Foreign Affairs Im. There was no minister called “Min” in the South Korean cabinet during van Gulik’s visit. Ockam’s razor, however, demands that we accept “Min”, as that is a regular Korean family name. I do not know what particular member of the Min clan van Gulik then refers to. I am not entirely sure whether the text actually says “Min. Min” however – it could also feasibly be read as “Mr. Min.”

73 I have not been able to identify this person.

Oktober 22, zaterdag

8.30 in stationwagon Airways van Chosen hotel naar Kinpo Airfield. 1.30 in Tokyo op Haneda aangekomen. (…)

October 22, Saturday

8:30 in the Airways station wagon of the Chosen Hotel to Kimpo Airfield. Arrived in Tokyo at Haneda at 1:30. (…)

Oktober 23, zondag

’s ochtends rapport over Korea opgesteld. (…)

October 23, Sunday

In the morning prepared report on Korea. (…)

P’iltam and Other Calligraphies Gifted to van Gulik

Calligraphic Works Preserved at Leiden University Libraries

List of Works

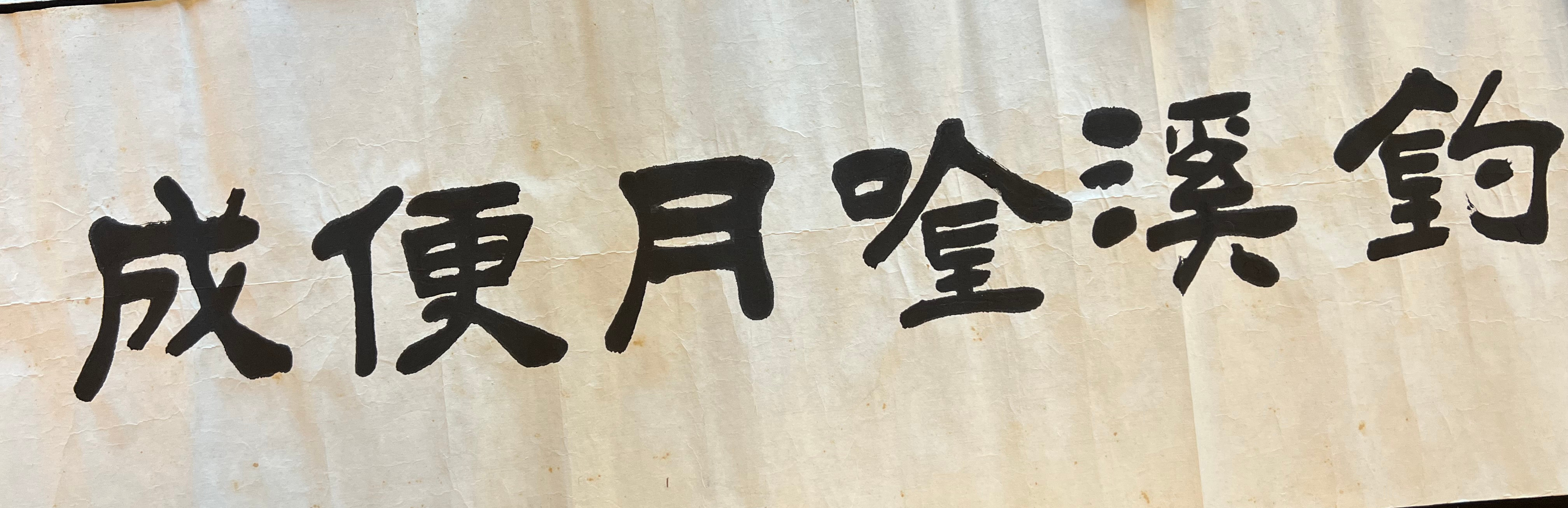

▶ 1. Calligraphy by An Chongwŏn (1874-1951), dedicated to RHvG. Text: 釣溪唫月便成翁. Dated 己丑 [1949]. Size 124 x 32 cm. Seal 觀水居士, another seal, plus one very peculiar seal at the beginning of the scroll.

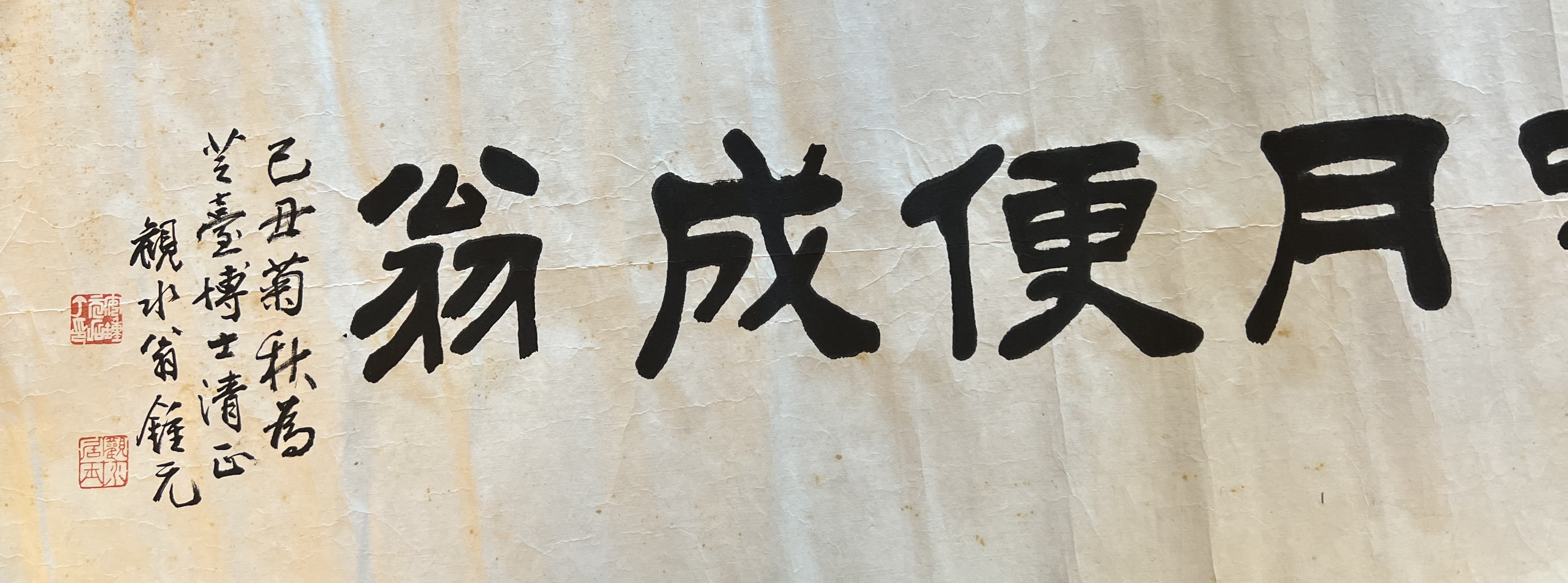

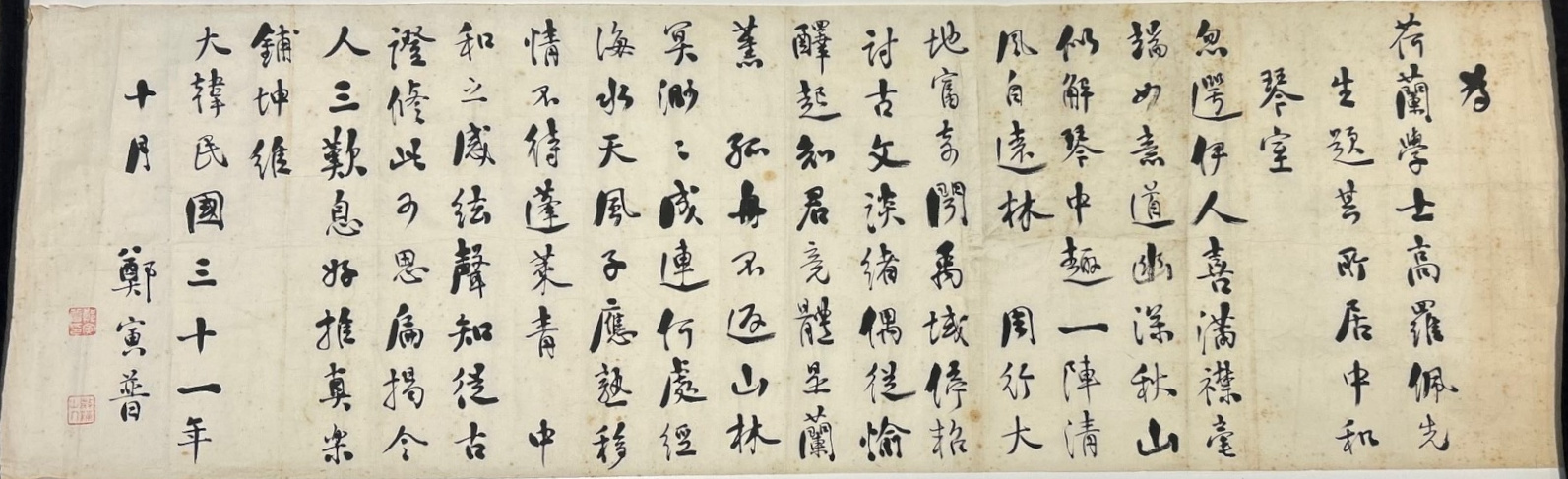

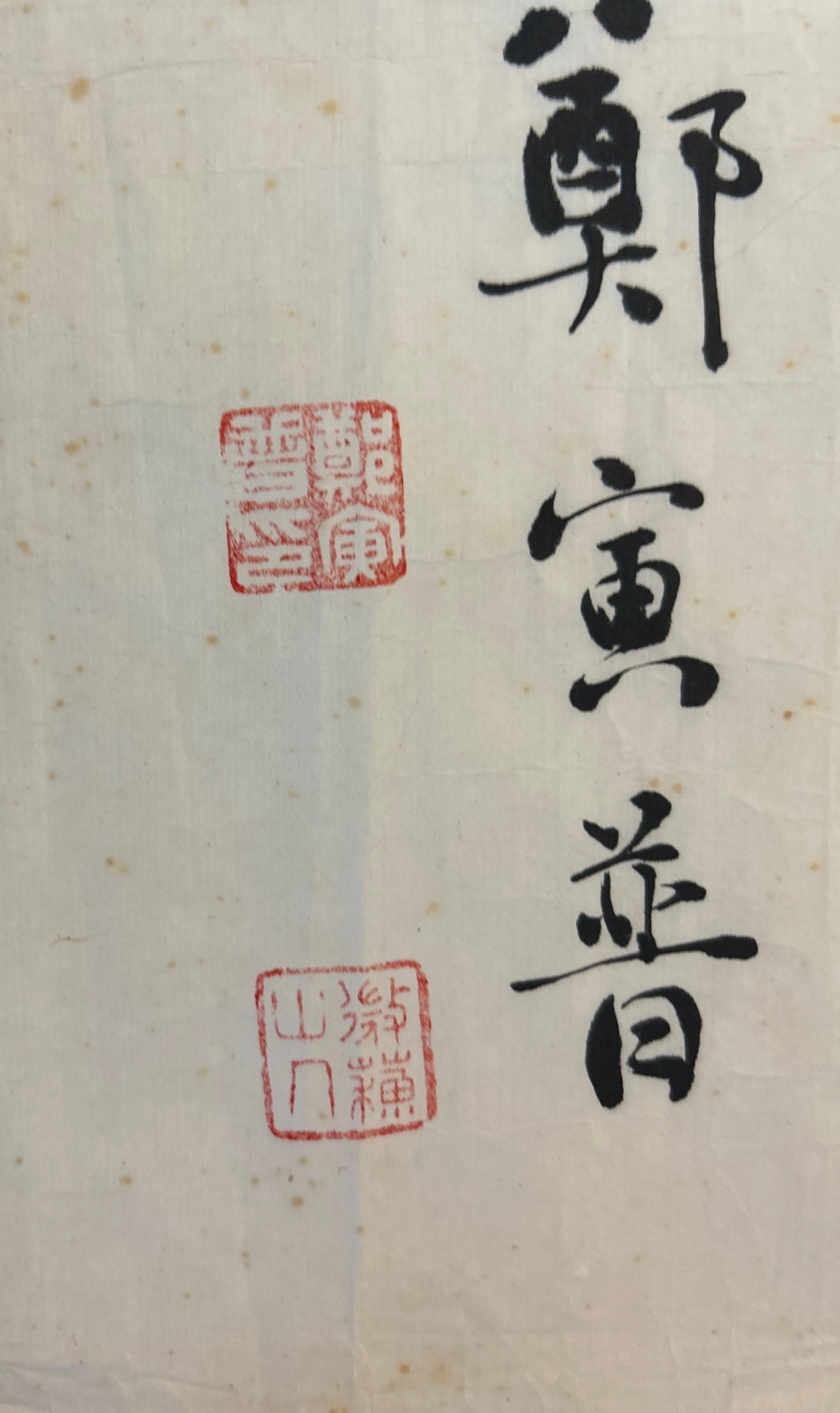

▶ 2. Poem with dedication to RHvG by Chŏng Inbo (1893-1950), dated October of the 31st year of the Republic of Korea 大韓民國31年十月. Korea. Long text about RHvG and his study.

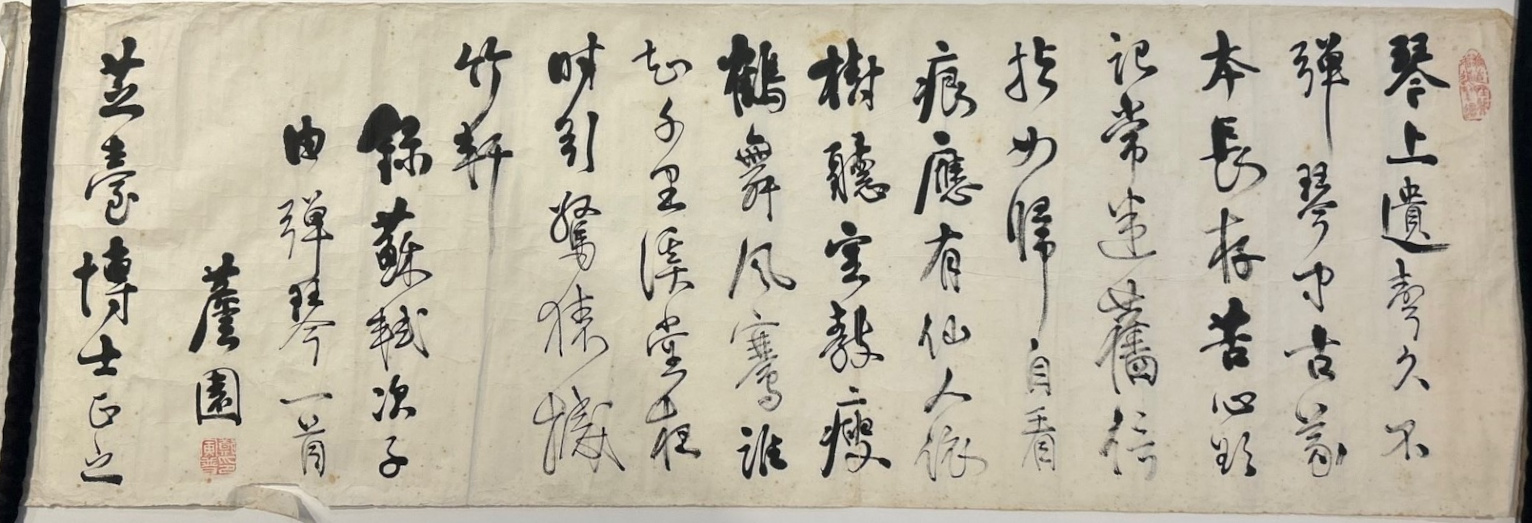

▶ 3. Poem with dedication to RHvG by Chŏng Inbo (1893-1950), Tamwŏn. Seal of Chŏng Inbo plus one seal with eight characters. Topic: lute music. Size: 101 x 33.5 cm.

中和琴室. Seal 鄭寅普印 and 薇蘇山人.74 Size: 110 x 33 cm.75

74 One of Chŏng Inbo’s literary pseudonyms was Miso sanin 薇蘇山人– the first character on the seal is hard to read, but the other three are quite clear.

75 The Wereldmuseum in Leiden also hosts several calligraphies and seals from van Gulik’s collection. Karwin Cheung wrote about these in his 2024 article: see Karwin Cheung, “A portrait of the scholar as intelligence operative.”

Context and Contents of the Works:

(1) An Chongwŏn: Poetic line

釣溪唫月便成翁.

Fishing the stream, chanting to the moon - thus I became an old man

The line appears to be derived from the Tang-dynasty poet Fang Gan 方干’s poem “Lament for the Jiangxi Recluse Chen Tao” (哭江西处士陈陶).

(2–3) Chŏng Inbo: Two poems

Apart from his study of calligraphy Robert van Gulik deeply studied the guqin (古琴), and created a study named Chunghwa kŭmshil 中和琴室 ("The Harmonious Zither Chamber"), where he continued to collect and research materials related to the ancient zither. What follows are the two poems that Chŏng Inbo presented to van Gulik, one composed specifically for the study Chunghwa kŭmshil, and another recording a poem by Su Shi 蘇軾.

Poem 1:

爲 荷蘭學士 高羅佩先生 題其所居中和琴室

忽遌伊人喜滿襟, 毫端如意道幽深.

秋山似解琴中趣, 一陣淸風自遠林.

周行大地富奇聞, 禹域停軺討古文.

談緖偶從愉醳起, 知君竟體是蘭薫

孤舟不返山林冥, 渺渺成連何處經.

海水天風子應熟, 移情不待蓬萊靑.

中和之感絃聲知, 從古證修此可思.

扁揭令人三歎息, 好推眞樂鋪坤維.

大韓民國 三十一年 十月

鄭寅普

When I met him, to my surprise,

joy billowed in my chest:

freely expressing his thoughts with his brush,

he plumbed the obscurest depths.

As mountains in autumn seem to open up

so did feelings from his qin,

a sudden fresh wind, blown

from faraway woods.

He circled this great globe,

rich with tales;

but in China, his journey paused

to discuss our ancient lore.

As the conversation flows

easily and joyfully,

I realized this gentleman’s essence

was pure as an orchid’s breath.

The lone boat doesn’t return,

hills and woods grow dim;

where did Cheng Lian’s76

76 This passage evokes the story of the famous guqin master Cheng Lian 成連 from the Spring and Autumn period. Cheng Lian set out to find his teacher, Fang Zichun 方子春, who was said to be at Mount Penglai in the eastern sea, in order to teach his disciple, Boya 伯牙, the art of playing the guqin in a way that could move people's hearts. However, upon reaching Mount Penglai, Cheng Lian, claiming he would bring his teacher, boarded a boat and sailed away, never to return. Boya, filled with sorrow and longing, played the guqin, pouring his emotions into the music. Eventually, he reached the highest level of guqin playing, expressing human emotions in a way that could deeply move others. This is a metaphorical expression of Robert van Gulik`s study and scholarly journey with regard to the guqin.

voyage end?

On sea waves, the sky breeze

you echo, sir;

the transfer of feelings

does not need the eternal green of Mt. Penglai.77

77 This can be interpreted as expressing the potential of music and scholarship to transcend the eternity symbolized by the greenness of Mount Penglai.

A sense of harmony (中和)

Is what the song of the strings knows…

The ascesis of yore:

this deserves long contemplation.

May the motto of his study inspire

three awestruck gasps.

It is fit to spread the true music

to the ends of the earth.

October, the 30th year of the Republic of Korea78

78 The ‘Republic of Korea’ era counts from 1919, the year of the proclamation of independence and the establishment of the Korean Provisional Government.

Chŏng Inbo.

Poem 2:

(written by Su Shi 蘇軾)

琴上遺聲久不彈,

琴中古義本長存.

苦心欲記常迷舊,

信指如歸自看痕.

應有仙人依樹聽,

空教瘦鶴舞風騫.

誰知千里溪堂夜,

時引驚猿撼竹軒.

錄蘇軾次子由彈琴一首

簷園

芝臺 博士正之

The qin’s echoes linger,

long untouched,

but the ancient meanings in it

still are handed down.

The mind strains, longing to remember,

yet always loses its way to the old melody.

But trust your fingers, and it is like going home,

you can still glimpse its traces.

Maybe there are immortals[gods]

leaning on trees, listening,

while a gaunt crane

sways aimlessly in the wind.

Who knows whether hundreds of miles off,

in a riverside pavilion by night,

sometimes a startled monkey

shakes the bamboo rails?

A poem by Su Shi, written in response to his younger brother Su Zhe’s qin performance, recorded by Tamwŏn (Chŏng Inbo) and presented to Dr. Zhitai.79

79 This was van Gulik’s literary pseudonym. It was derived from the name of the location of the Dutch embassy in Tokyo: Shiba-dai, of which the characters in Chinese pronunciation are read Zhitai.

Analysis of the Two Poems and Their Significance

Chŏng Inbo’s poems do not merely praise van Gulik as a foreigner capable of deeply understanding and performing ancient music; rather, they address him as a scholarly subject who can comprehend the to (道) of the kŭm (琴) and the normative rules of mun (文). Images such as “autumn mountains” (ch’usan 秋山), “distant forests” (wŏllim 遠林), “clear winds” (ch’ŏngp’ung 淸風), “heavenly winds” (ch’ŏnp’ung 天風) and “orchid fragrance” (nanhun 蘭薫) are not expressions of purely personal emotion, but motifs long accumulated within the tradition of classical Chinese literature. The same is true of the allusions to Cheng Lian and Boya, paradigmatic figures of musical understanding and sympathetic resonance. The motif of the “lone boat” (koju 孤舟) also evokes the story of Cheng Lian and Boya, in which solitude leads to a deeper level of musical understanding. By drawing on such classical stories, the expanded imagery and narrative allusions would likewise have generated a deep sense of resonance between the two scholars. These elements further reinforce this shared symbolic vocabulary. The harmonious balance at the core of all action and thought—namely, chunghwa (中和)—not only designates the name of van Gulik’s study, but also functions as a shared value order through which its deeper significance is jointly recognized and understood.

Through these shared references, the two figures would have resonated with one another both literarily and emotionally. And the line “the transfer of feelings does not need the eternal green of Mt. Penglai” may be read as indicating that civilizational understanding does not rely on transcendent utopias or mythic fantasies, but instead situates cultural exchange between a Westerner and a Chosŏn intellectual firmly within the realm of lived reality. Moreover, the fact that Chŏng Inbo presented van Gulik with a kŭm-related poem by Su Shih was not simply because van Gulik was a Western diplomat, but because he was already a figure who had understood and enacted the order of mun and kŭm. Van Gulik was not only someone who took Chinese traditional culture as an object of study; he was a Western intellectual who actively sought to internalize the lifestyle and cultural practices of the classical literati-officials. His sustained engagement with calligraphy, seal carving, painting, and the guqin (古琴) may be understood as going beyond the realm of personal hobby, approaching instead a practical effort to integrate himself into a particular set of civilizational norms.

Van Gulik’s book Lore of the Chinese Lute encapsulates this orientation in a concentrated form. In this work, van Gulik understands the guqin not as a mere musical instrument, but as a cultural apparatus in which literati self-cultivation, ethical reflection, and perceptions of nature are condensed. In order to convey this understanding to Western readers, he adopted a careful and deliberate strategy extending to translation, annotation, and even the selection of conceptual terminology.

It is against this background that Chŏng Inbo’s attempt to converse through the civilizational language of Su Shih’s poetry may be understood. Su Shih’s poem centers on the idea that even when the kŭm has not been played for a long time, the “ancient meaning” (koŭi 古義) embedded within it does not disappear, and that tradition is transmitted not through memory or abstract concepts, but through the tactile knowledge of the hands and embodied practice. While ostensibly a poem about music, it is at the same time a meta-level reflection on cultural transmission and modes of understanding.

In this sense, the poem can be said to overlap with van Gulik’s own identity. He was a figure who, even after Chinese civilization had lost its political power and authority, possessed a profound understanding of its cultural and ethical order, and who further extended that understanding to Korean culture, actively seeking to learn it. To present him with Su Shih’s poem, therefore, can be interpreted not merely as viewing van Gulik as a “Westerner who studies East Asian culture,” but as an act of recognizing him as a scholar capable of sensing the lingering resonance of tradition and grasping its significance.

O Sech’ang’s Calligraphy at the Wereldmuseum Leiden

O Sech’ang: Text for the Dutch Scholar Gāo Luópèi, presumably written for a signboard (plaque) for his study "Chunghwa kŭmshil" ("The Harmonious Zither Chamber")

中和琴室.80

80 While “chunghwa” is a well-known word which means “harmony”, it is simultaneously a play on words, referring to Robert van Gulik’s sophistication as a scholar of ancient China (chung 中) and his Dutch ancestry (hwa 和, as in Hwaran 和蘭).

芝臺先生正謬 檀紀四二八二年冬 韓京老布衣 吳世昌

Dedicated to Master Zhītái. Winter of 1949. O Sech’ang, an old scholar residing in Seoul

O Sech’ang who produced this inscription for the Dutch scholar “Gāo Luópèi”, intended for the signboard of his study Chunghwa kŭmshil (“The Harmonious Zither Chamber”), devoted himself to the study of seal script (篆書) and archaic pictographic forms (象形古文), and developed a distinctive calligraphic style that foregrounded the visual form of characters and the structural strength of their brushstrokes. Rather than producing a merely functional inscription, he created a carefully composed work in a pictographic script that reflects both scholarly refinement and visual deliberation. This calligraphy is part of the collection of the Wereldmuseum in Leiden.81

81 It was catalogued there under this call number: RV-5265-10.

P’iltam: Cultural Exchange beyond Political Language

These encounters, in which p’iltam and calligraphic works were exchanged, can be reconstructed on the basis of van Gulik’s diary. They are also situated within a broader context by the Chayu sinmun 自由新聞 article of October 21, 1949—in one of two South Korean newspapers published after liberation—which shows these exchanges within a broader context. With the subheading “Even Master Widang was speechless” (爲堂 先生도 啞然), the article introduced a Dutch scholar–diplomat, described as an “eminent guest of the academic world,” who had come to Korea to study its ancient culture, and reported that he had long pursued research in East Asian studies. News reports placed particular emphasis on van Gulik’s meeting with Master Widang Chŏng Inbo and included a photograph showing him engaged in scholarly exchange at the home of Chŏng Inbo. In this interview, Robert van Gulik stated that he was conducting research on Kojosŏn and on ancient Korean music, particularly the kayagŭm. Given his profound expertise in the kŭmdo (琴道, the way of the zither), this attests to his deep interest in Korea’s kayagŭm tradition as well. The photograph taken at Widang’s residence depicts van Gulik practicing calligraphy, suggesting that the two men conversed with one another in this way.

By the mid-twentieth century, munŏn (文言, Classical Chinese) had lost its status as an international lingua franca, and p’iltam likewise had ceased to function as an institutionalized and customary mode of communication. The regions of East Asia no longer employed Literary Chinese as a transnational common script, and with the formation of modern nation-states, Western scholarship and vernacular prose styles became the new standards for knowledge production. Against this backdrop, the fact that Chosŏn intellectuals chose the forms of poetry and calligraphy in their encounter with van Gulik indicates that these media could still operate as viable tools for recognizing and positioning the other as a scholarly subject.

From a functional perspective, the calligraphic works and poems that An Chongwŏn, O Sech’ang, Chŏng Inbo presented to van Gulik possess a p’iltam-like character insofar as they employ poetry and prose as a medium of communication. This was neither a question-and-answer exchange conducted within the framework of official diplomacy, nor an extension of institutionally guaranteed literati interaction. At the same time, it would have been inappropriate to reduce this exchange to a mere personal tribute or a hobbyist exchange of calligraphy and painting. This mode of communication differed in a crucial respect from premodern p’iltam. Whereas written conversations between Chosŏn and Ming–Qing China or Japan took place within a shared munŏn civilizational sphere, in the case of Chŏng Inbo and van Gulik, van Gulik as a Westerner—previously perceived as external to that sphere—, entered it by learning and performing its rules from the outside. Rather than treating van Gulik as a representative of diplomatic power or as a proxy for Western civilization, Chŏng positioned him as a scholar capable of responding to the norms of mun (文). Van Gulik, in turn, possessed the cultural competence and disposition required to respond to such an evaluation.

According to press reports, Chŏng Inbo and van Gulik appear to have been able to communicate at a basic level in Korean. Nevertheless, Chŏng’s choice to respond through the traditional forms of classical poetry and calligraphy should be understood not as a matter of linguistic necessity, but as a deliberate selection of the level and mode of communication. Might p’iltam, then, be understood as a tool through which intellectuals could position themselves as cultural subjects under conditions in which political language failed to operate? This perspective may also help explain why, according to interviews, van Gulik in 1949 continued to display a cautious attitude in his encounters with intellectuals. This was not only due to memories formed before liberation, but also because the international and domestic instability confronting Korea persisted even after liberation. In 1949, Korea was formally an independent state, yet within the international order it remained positioned at the periphery. Although the Republic of Korea was established in 1948, it was not recognized as one of the victorious powers of the Second World War and was excluded from the central processes of managing Japan’s defeat and restructuring the postwar order. While the historical legitimacy of anti-Japanese resistance was acknowledged to some extent on moral and narrative grounds, it did not translate into substantive voice within an international system structured around international law, military power, and diplomacy dominated by the great powers that shaped the postwar settlement.

The individuals involved each perceived these international conditions from their own positions. Van Gulik’s perspective, as a diplomat visiting Korea, was faithfully reflected in his official reports. In this process, cultural exchanges and p’iltam with Korean intellectuals, though personally meaningful to him, were deliberately excluded from the framework of diplomatic judgment and policy reporting. By contrast, the conditions of speech confronting Korean intellectuals under the same circumstances were fundamentally different. In this context, p’iltam and mun were not alternatives to politics or diplomacy, but spaces in which intellectuals could position themselves as cultural subjects precisely under conditions where political and diplomatic language no longer functioned—although such cultural practices, to be sure, could not in themselves overcome the asymmetries of the international order.

In the post-liberation international order, Korean intellectuals such as Chŏng Inbo—despite their profound scholarly authority—found themselves structurally marginalized within the arenas of diplomacy and politics. Chŏng Inbo, moreover, stood in a tense relationship with the Rhee government, which may have further constrained his position within the emerging political order. It was against this backdrop of marginalization and constraint that such an encounter assumed particular significance. Under conditions in which the subject of the international order had shifted to the West, the fact that a representative of that West engaged in exchange through the languages of East Asian civilization—poetry and music—may have carried particular significance for intellectuals who were likely experiencing a sense of loss. To be sure, the asymmetries of political power were not resolved within the space governed by the rules of mun (文); yet those asymmetries were, for a brief moment, suspended. In this sense, the encounter may be understood as a cultural event in which, amid the fractures of a civilizational transition, Korean intellectuals were able to momentarily reaffirm their dignity.

This divergence between cultural exchange and diplomatic purpose becomes particularly clear when we place these encounters alongside van Gulik’s official reports. The question undergirding a broader appraisal of van Gulik’s visit to Korean intellectuals such as Chŏng Inbo in the guise of a holiday trip is to what extent his intellectual activities aligned or perhaps clashed with the diplomatic objectives of his visit. A short analysis of van Gulik’s official report to the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs is in order then.

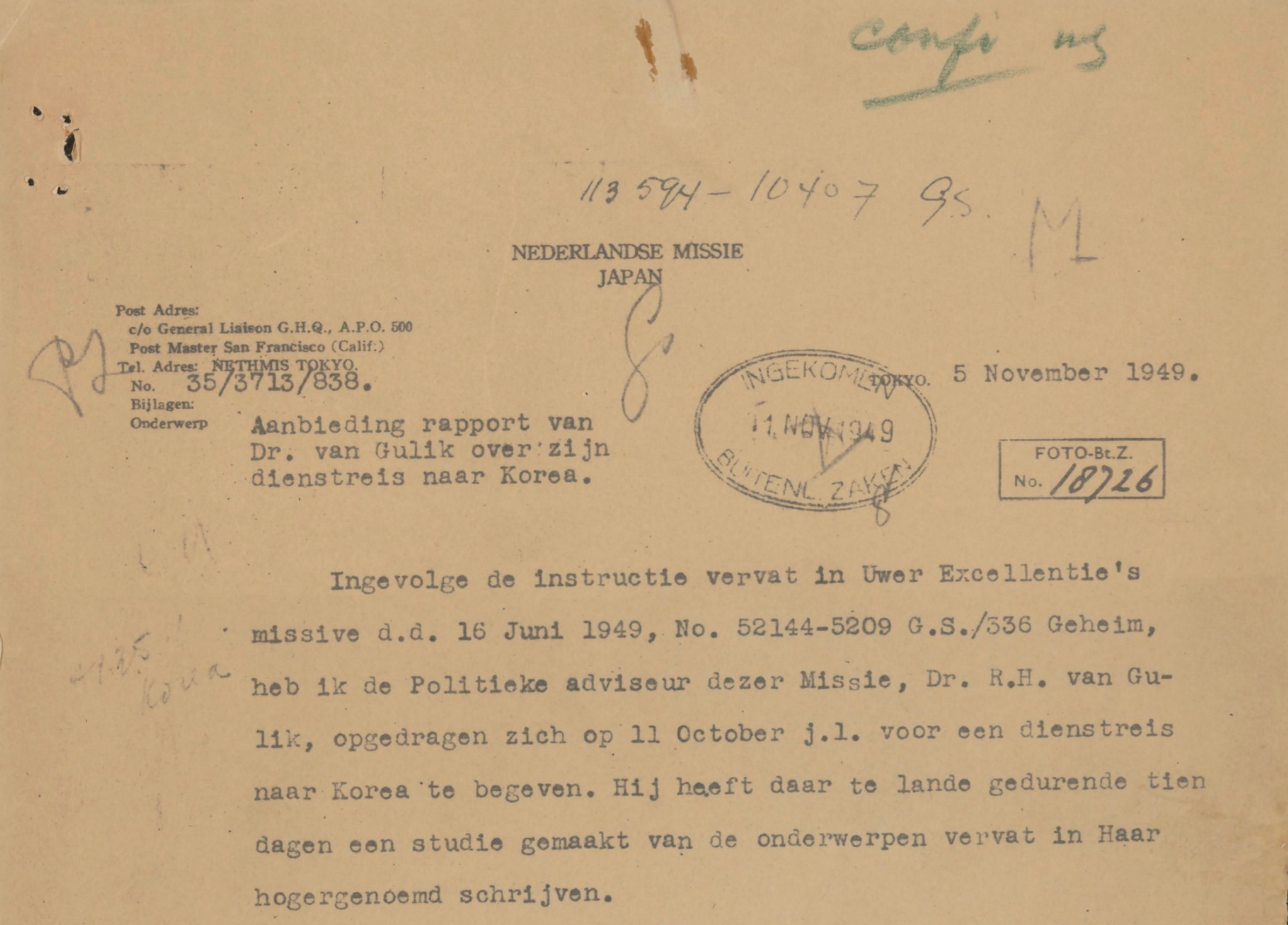

The diplomat writes

The report for the benefit of the Minister of Foreign Affairs that van Gulik wrote, apparently in one morning right after he returned,82 tells the story of an experienced diplomat visiting a potential ally of the Netherlands amidst difficult and unstable circumstances. The cover letter to the report was written by H. Mouw, Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador to Japan. The tone of that is somewhat patronizing towards the young Republic of Korea but also betrays concern. It is patronizing in its undiplomatically displayed lack of understanding of South Korea’s difficult position as a recently divided post-colonial country. It displays concern over Seoul’s savvy economic politics: Seoul is interested in relations with the Netherlands, but mainly, it seems because it was economically interested in Batavia (present-day Jakarta). Although in 1949, Batavia was still part of a Dutch colony, Seoul did not expect this to last much longer. As such it made it clear that it would then (also) establish economic relations with Indonesia. The letter finally mentions the conclusion van Gulik had also reached: establishing fully staffed and equipped embassies would be a financial burden for both countries, so frequent mutual visits was the way forward for the time being.83

82 See the entry for October 23, 1949.

83 H. Mouw, “Aanbieding rapport van Dr. Van Gulik over zijn dienstreis naar Korea,” pp. 1-4. In “Rapport van de politiek adviseur van de Nederlandse Missie in Japan over zijn dienstreis naar Korea, met geleidebrief,” Nationaal Archief. Inventaris van het archief van de Commandant Zeemacht in Nederlands-Indië, (1942-) 1945-1950, 2.13.72, Inventarisnummer 1441.

As mentioned before, and as noted by Karwin Cheung, van Gulik made his trip under the pretence of going on a private holiday trip.84 In reality, as the report states on its first page, van Gulik and the Dutch ambassador found it wise not to make this an official trip, because South Korea “had a well-organized routine to ‘show around’ foreign visitors.” It was feared that Seoul’s proactive attitude would get in the way of a fact-finding mission such as this. Van Gulik was tasked with finding out what the political, economic, and diplomatic situation in Seoul was like. A further concern was that sending an official Dutch mission to Seoul from Tokyo would create the impression that the Dutch government still saw South Korea as subservient to Japan – this it wanted to avoid at some cost.

84 See Cheung, p. 85.

85 Van Gulik, “Rapport”, p. 4-7. This notion echoes the Japanese colonialist notion of “gai’atsu no rekishi” or “history formed under foreign pressure.” See Breuker, “Contested Objectivities”.

The report continued with an introduction of the present political, economic, and diplomatic circumstances. To that end, van Gulik provides a bird’s eye overview of Korean history, culminating in the establishment of the Republic of Korea in 1948. This historical summary is, given van Gulik’s stature as a leading scholar on Japan and China, perhaps disappointing in that it is a recapitulation of the Japanese colonialist view of Korea as a geographically unfortunately positioned culture, bound to be dominated and fought over by the greater powers in its vicinity.85 Van Gulik repeats some of the staple notions of colonialist historiography here: the historical subservient position of Korea vis-à-vis China, later replaced by Japan and Russia (p. 4), its fundamental political fragmentation which obstructed in his view effective resistance against the Japanese and now made the US South Korea’s obvious “guardian” (p. 10). He notes the stark political division within the Korean peninsula and within South Korea itself, yet fails to come to the realization that perhaps the colonial period was an important factor in the emergence of different kinds of political radicalization and indeed in the division of the peninsula itself. When he discusses the economy of South Korea, however, he does recognise the “division of North and South as the core problem that disrupted economic life” (p. 36). Traces of Wittfogel’s essentialist Orientalism shine through when Syngman Rhee is described as an “unadulterated Asian despot” (p.8).

Van Gulik’s sharp eyes do not miss the problems of the Rhee administration, its corruption, its unrealistic assessment of its own strengths vis-à-vis North Korea, the fraught security situation within South Korea (pp. 14-20). At the same time, he writes down how he reached out to opposition figures, just in case “the Rhee government would leave the stage.” (p. 19). He shows an acute sense of the military situation when he mentions the 12,000 North Korean troops fighting in Manchuria for the Chinese communists and what would happen to the equilibrium on the Korean peninsula when they would return (p. 21), but lacks the sense of urgency that, perhaps in hindsight, might be expected, given the outbreak of the Korean War a mere eight months later. A potential outbreak of hostilities is not treated seriously in the report.