Eastside Story: the Pan-East Sea Culture Area discourse in South Korean archaeology and proto-history

The Pan-East Sea Culture Area (PESCA) is a South Korean discourse of archaeology that elaborates material connectivity between eastern Korea (Gangwon Province and the Tumen River basin), and continental regions to the north and northeast beyond. The temporal scope stretches from the mid-Neolithic (c.4500 BCE) to early centuries CE. As a discourse, it is representative of current interest by South Korean scholars in regions that extend beyond the conventional boundaries of early Korea. However, PESCA is distinct for its focus on the remote eastern vectors transecting the Korean Peninsula and continental Manchuria, regions that are underrepresented in traditional and current discourses of the early past. A characteristic and tension within PESCA discourse is that it bridges between a transnational archaeology on the one hand, and concerns of orthodox Korean history on the other.

This article examines PESCA discourse with attention to both emic and etic perspectives. The emic foregrounds framings and significances of PESCA as articulated by leading authors, Kang Inuk and Kim Chaeyun, and as viewed from a South Korean perspective. The etic highlights additional functions and implications, situated across both Korean and PESCA-centered perspectives. PESCA is not just a framework, but an argument. It evinces a material prehistory of the eastern groups, including Okchŏ, Ye, Yilou (K. Ŭmnu) and Mohe (K. Malgal), named in sources yet treated as a minority other to west-centered trajectories of development. Tracing material developments to the Neolithic, a PESCA-centered perspective interprets these peoples as autonomous actors of their own networked space.

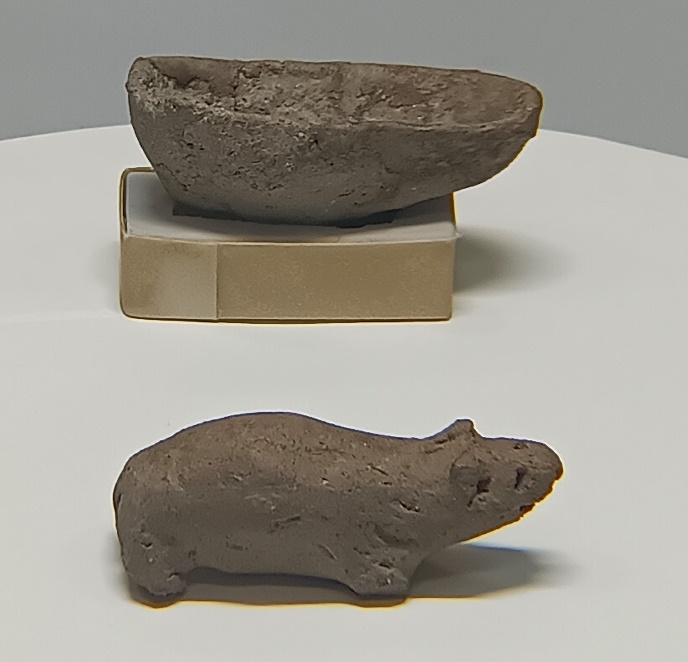

Sea lion or bear? Located at Yangyang, on the east coast of Gangwon Province, the Osalli Neolithic Site Museum makes much of two clay sculptures. One is interpreted to be a human face, making it possibly the earliest sculptured representation of a face in Korea. The other is an animal that lies on its front with short legs and a smiling face (Figure 1). The display labels this figurine as a bear (kom). For most visitors this will readily accord with a popular association of bears to early Korean history that derives from the myth of Tan’gun—founder of Old Chosŏn, the much celebrated supposed first state of Korean history—being born to a bear-turned-woman. However, in a 2017 study, Kim Chaeyun, an archaeologist with experience in the Russian far east, argues the figurine is not a bear but a sea lion.1 This interpretation has less association with Korean tradition but instead aligns Osalli with an East Sea coastal ecology; it is supported by a third clay model of a dugout boat. Through her interpretation, Kim accords the early communities of Osalli an eastern identity distinct from conventional Korean associations, such as the Old Chosŏn foundation myth.

1 Kim, Chŏpkyŏng ŭi aident’it’i, 50. Kim in fact uses the term for “seal” (mulgae) however, the figurine clearly has external ears, while a seal does not, making it closer in resemblance to a sea lion (kangch’i).

2 Kang, Okchŏ wa ŭmnu.

3 The Korean term that I translate here as “culture area” or “culture sphere,” munhwagwŏn 文化圈, is originally a Sinitic calque of the German term Kulturkreis (“culture circle”), that was used in German language anthropology and archaeology from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century. See Rebay-Salisbury, “Throughts in Circles.” Elaborated below, however, Kang Inuk uses munhwagwŏn and close variants as a translation of the English term “culture area” used in North American anthropology, that is conceptually distinct from European Kulturkreis. In the context of PESCA discourse, munhwagwŏn becomes its own concept defined through Kang and Kim Chaeyun’s usage and elaboration.

Okchŏ and Yilou. In 2020, prominent archaeologist, Kang Inuk, published a book aimed at popular readership titled after two proto-historical entities located in the far northeast, Okchŏ 沃沮 and Yilou (K. Ŭmnu) 挹婁.2 While Okchŏ is traditionally viewed as a part of Korean history, the Yilou, who were located further north and beyond current-day Korea, are not. Revising such historical tradition, Kang argues that the Yilou, too, should be treated as a part of Korea’s past. However, rather than simply claim Yilou as an expanded part of Korea, he simultaneously groups Okchŏ, Yilou, and other eastern peoples as part of a wider “Pan-East Sea Culture Area” (hwandonghae munhwagwŏn).3 The archaeology of this culture area notably extends into Gangwon Province and wider Central Region (Chungbu) Korea, where for the late-Iron Age period, it is known as the Chungdo Type (Chungdo sik) culture.

Central Korea and maritime Siberia. In a review of South Korean discourses of Central Region archaeology in the Late Iron Age, Hari Blackmore critiques a common interpretation in which Chungdo Type archaeology is equated to one side of a supposed east-west ethnic dichotomy between Yemaek 濊貊 and Han 韓 peoples, respectively.4 In this context, he cites Kang and other scholars’ elaboration of connectivity between central Korea and “maritime Siberia” as exemplifying a model of broader interactional networks within which, Blackmore argues, Central Region archaeology would be better situated.5

4 Blackmore, “Critical Examination,” 104.

5 Blackmore, “Critical Examination,” 113–114.

The “Pan-East Sea Culture Area” (PESCA), that is the subject of this article, is an interpretative label applied to material archaeology found along the eastern coastline and interiors of Korea, Russia and northeastern China. Over the past century, this archaeology has been separately investigated by the different countries across which modern borders it occurs. First synthesized by Japanese scholar, Ōnuki Shizuo during the 1990s, in more recent years the totality of this archaeology has become a topic of interest to South Korean scholars. This is for several reasons. Most immediately, the archaeology appears to show a connection between the Gangwon Province region of the central Korean peninsula and continental maritime Siberia. This connection has significance to (South) Korea as it has been interpreted to offer clues to, for example, the origins of the Korean Bronze Age, and for later periods to represent the archaeology of early entities (peoples or polities) named in Korean tradition, such as Ye 濊 and Okchŏ, that are associated with the central east and northern east (Hamgyŏng Province) of the peninsula, respectively.

From a South Korean perspective this material connection to archaeology in Russia has further appeal on a pragmatic level as it helps compensate for the inaccessibility of corresponding archaeology in North Korea and China. From the mid-1990s and especially 2000–2010s Russia has provided South Korean scholars opportunities for collaboration at a time when disputes with Beijing over claims to early history began to foreclose prospects of collaboration and caused the curtailment of access to sites in China.

The Russian far east connection, meanwhile, has encouraged and enabled South Korean scholars to conceptualize an ‘eastern archaeology’ autonomous from predominant west-centric dynamics of history and politics. Geographically, Korea’s west has the most direct connectivity (or exposure) to China and the Steppe; it has therefore been understood as the traditional route of civilizational influence. Within the peninsula, the west, and secondarily southeast, have also been the centers of early and all subsequent states and modern conurbations, from the Three Kingdoms Period to the present. The east therefore provides interest as a lesser studied yet integral region, while any significance it can be attributed has the potential to balance China and Steppe-centric hegemonies in the narrative of Korea’s early past.

Awareness of eastern archaeology is established within the South Korean archaeology field though is still a minority discourse. Writings that adopt the Pan-East Sea Culture Area (PESCA) framework are a specific sub-discourse of this broader yet minority interest in eastern connectivity. Among several scholars working with data and ideas pertinent to PESCA, two have contributed most to its elaboration: Kang Inuk, who has done most in articulating the theory and popularizing the notion of PESCA, and Kim Chaeyun, who has has contributed significantly to its empirical substantiation.

With the focus on PESCA, this article treats the written analysis of archaeology as discourse. I argue discourse provides us a unit by which to examine from a meta-perspective the practiced understanding of a given topic, namely, eastern connectivity as interpreted through PESCA. Here, we may note that PESCA and the broader interest in eastern archaeology are themselves one part of a wider discourse in South Korean archaeology that examines regions of Asia that either extend or are located beyond the conventional boundaries of early Korea. This discourse I term Korean Early Asia.

As spatially conceived, the Pan-East Sea Culture Area comprises a vast region extending from the mountains and coastline of Gangwon Province, northeastern South Korea, in the south to the Lower Amur River and parallel eastern coastline in the north. The key idea of PESCA is that this region has played host to common modes of life (subsistence patterns) that have given rise to a shared material, and possibly cultural or ethnic, identity for the people who lived there. This cohesion is premised on three factors: (1) common geography and climate, (2) interconnectivity within the zone, and (3) collective autonomy of the zone from regions to the west owing to its geographic remoteness.6 The chronology of PESCA begins with the first evidence of connectivity in the mid-Neolithic; it continues through the Bronze Age to the emergence in the Iron Age of archaeology associable with early entities named in historical sources; it presumes to end with the subordination of these entities to west-centered states, chiefly Koguryŏ (c. 1 – 668 CE).

6 Regions west include: western Korea, southern Northeast China (Manchuria) west of the Mudan River basin, Central Plain China, and the Eurasian Steppe.

In order to elaborate the discourse this article alternates between emic and etic perspectives. The emic perspective presents framings and topics of PESCA fully articulated within the publications of Kang and Kim. The etic perspective is my own outside analysis that highlights additional meta-functions and significances. The sections unfold below beginning with a stronger emic focus and conclude with etic analysis. However, for our purposes, emic and etic are not mutually exclusive. There is overlap in both directions: the emic representation is filtered through my own framing (my framing of their perspective) and elaboration, while most points of the etic analysis are touched on, or alluded to, within Kang and Kim’s writing.

The conceptual development of PESCA

Kang and Kim have each authored short overviews of PESCA that start from the Neolithic and survey chronologically forwards in time.7 As an idea, however, PESCA was initially conceived with a focus on the Iron Age and proto-historical period of transition to early history. Its temporal scope was then expanded back to encompass archaeology of the preceding Bronze Age and Neolithic periods. PESCA thus was first developed in the early 2000s as a framework to explain material similarities observed between the iron-age period archaeology of central Korea (Gangwon Province), namely Chungdo Type archaeology, and the Krounovaka Culture of southern Maritime Province Russia.8 Another contributor to the discourse, No Hyŏkchin, first termed this model of Iron-Age connectivity an “Eastern Road” (tongno) before Kang named it the “Pan-East Sea Prehistoric Culture Area” (hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn).9

7 Kang, “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn,” 429–450; and Kim, “Hwandonghae munhwagwŏn ŭi yŏksajŏk chomang,” 125–142.

8 No, “Chungdosik,” 101–104; Subotina, “Ch’ŏlgi sidae”; and Kang, “Ch’ŏngdonggi sidae ch’ŏlgi sidae.”

9 Kang, “Ch’ŏngdonggi sidae ch’ŏlgi sidae,” cited in “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn,” 429.

10 Kim “Hanbando kangmok t’oldaemun t’ogi” (2003), and “Hanbando kangmok t’oldaemun t’ogi” (2004).

11 Kang, “Tuman’gang yuyŏk ch’ŏngdonggi.”

12 Kim, “Hwandonghae munhwagwŏn ŭi chŏn’gi sinsŏkki,” “P’yŏngjŏ t’ogi munhwagwŏn,” and “Hwandonghae munhwagwŏn ŭi yŏksajŏk chomang”

13 Kang, “Malgal charyo,” 159.

14 Kim, “Hwandonghae munhwagwŏn ŭi yŏksajŏk chomang,” 136.

Around the early 2000s, Kim Chaeyun had separately been working on “augmented notched-rimmed” (kangmok toldaemun) earthenware, a type of pottery connected to the early Bronze Age. In South Korean archaeology, the conventional marker of the peninsular Bronze Age is not bronze itself, but mumun (“plain patterned”) pottery, for which notched-rimmed pottery is regarded as a precursor. While others have located the origins of notched rimmed—and by implication mumun—pottery in the northwest, Kim argued for its origins in the Tumen River basin, in the northeast, thus according the remote northeast region a central role in initiating the Korean Bronze Age.10 Kang also published on similar archaeology of the Tumen Basin region,11 before both expanded the temporal limits of PESCA back to the Neolithic with Kim discussing the earliest examples of connectivity between Gangwon Province (South Korea) and the northern limits of PESCA, and Kang the development of Neolithic agriculture.12 In this way, PESCA discourse emerged as an interpretative framework for eastern archaeology focused on the Iron Age and identification of proto-historical entities, before being expanded backwards through time. More recently Kang has also hinted at expanding the frame further into the early historical period to account for east archaeology and peoples of the early historical Three Kingdoms and Silla periods.13 Kim also suggests that PESCA reconstitutes under the state of Parhae (698–926).14

Part 1: conceptualizing PESCA through the writings of Kang Inuk and Kim Chaeyun

Emic problematization: material connectivity and disconnected data

Aside from the two surveys, most other writing constitutive to PESCA focuses on specific time periods. Across Kang and Kim’s work, for all and any given period the broadest problematization of the archaeological data (and consequent rationale for PESCA) is premised on the following two points: 1) there is evidence of mid- to long-range material connectivity between the eastern central Korean Peninsula, specifically the region that falls within South Korea, and the continental northeast; and 2) this evidence is, however, fragmentary (tanp’yŏnjŏk)—owing to its paucity—while being more fundamentally fractured, or disconnected, due to it having been unearthed in different countries, and during differing periods and conditions of modern archaeological practice.

Discussing archaeology of the mid-Neolithic, the earliest phase of PESCA, Kim (2015) presents the evidence and problem as follows. Two types of earthenware occur along the east coast of Gangwon Province, South Korea, that exhibit connectivity to the north: burnished redware, and raised-line patterned earthenware.15 These pottery types have correlates in the far continental north, redware occurring among sites belonging to the Malyshevo Culture on the Lower Amur, and raised-line earthenware among coastal sites of the Rudnaya Culture. At the site of Osalli (Yangyang, Gangwon Province), redware occurs on the Korean east coast without evidence of preceding pottery tradition. The starting dates of the Malyshevo and Rudnaya cultures, meanwhile, each predate the occurrence of redware and raised-line pottery in Korea. These circumstances alone point to the two earthenware types having each originated in the continental north and thence been introduced to Korea, thus constituting two early cases of long-range connectivity. The problem, according to Kim—and that her work goes on to address—is that the wider respective material cultures (contexts) in which the potsherds occur have not been systematically compared. As a consequence the connectivity has yet to have been analysed at any greater level of material context than the potsherds themselves.16

15 Kim, “P’yŏngjŏ t’ogi munhwagwŏn.” At the site of Osalli (Yangyang), redware was newly discovered at the lowest stratum, followed by Osalli Type pottery, and then raised-line ware. At Jungbyeon (Chungbyŏn, North Gyeongsang Province) redware occurs mixed with Osalli Type.

16 Kim, “P’yŏngjŏ t’ogi munhwagwŏn,” 6.

For the period representing the transition to the Bronze Age, the spatial scope of PESCA connectivity narrows from Gangwon Province and the far north, to instead center on three adjoining sub-regions: the Tumen Basin, the Mudan and Muren river basins extending northwards in China, and the southern Russian Maritime Province (Primorye) to the east. Although contracting in distance, the data for this period is more complex because the region involved, and the Tumen Basin alone, transects three current states (North Korea, China and Russia) while from the perspective of South Korean scholars, further needing to be integrated into the analytical context of a fourth, South Korea.

For this period, North Korean sites on the Tumen are an original point of interest to South Korean archaeology but also the biggest challenge. They are important for two reasons. First, as a part of the divided peninsula, northern Korea falls, at least in principal, within the conventional purview of South Korean “Korean” archaeology. Second, documented sites on the North Korean (southern) side of the Tumen region provide some of the earliest known data for this particular period. One site in particular, Sŏp’ohang, is of singular importance for the wider region as it comprises a rare multi-level sequence of layers with differing pottery occurring in different layers.17 Sŏp’ohang is thus crucial for providing a relative chronology of this period. No equivalent site is yet known in the region outside of North Korea.

17 Kim, “Sŏp’ohang yujŏk.”

18 Kang, “Tuman’gang yuyŏk ch’ŏngdonggi,” 52, and “Tongbuk asiajŏk kwanjŏm,” 393.

However, due to North Korea’s inaccessibility to South Korean scholars, knowledge of the sites and artifacts is limited to North Korean authored reports produced in the early 1960s. These reports were based on excavations conducted in the latter 1950s in collaboration with Soviet archaeologists, and represent an early flourishing of archaeological practice in North Korea. However, the quality of the reports are by today’s standards rudimentary, and no further known excavations have been conducted in the region for archaeology of this same period since.18 Sŏp’ohang itself appears to have since been submerged under a reservoir.

Kang and Kim’s solution to this challenge is to compare the North Korean data with that of more recently excavated sites in China and Russia, premising that a common archaeology extends throughout the Tumen triangle region.19 However, a problem then arises in integrating archaeology of differing national practices and units of analysis. This is articulated by Kang as follows. South Korean archaeology has failed to develop a framework that could incorporate transnational data. While South Korean archaeology works at a smaller scale of “assemblages” (yuhyŏng) and “types” (sik – styles and morphologies), both Chinese and Russian archaeology use the larger conceptual unit of “material culture.”20 North Korean data, meanwhile, simply reports on individual sites and thus lacks any integrative frame.

19 Kang, “Tuman’gang yuyŏk ch’ŏngdonggi,” and “Tongbuk asiajŏk kwanjŏm”; and Kim, “Sŏp’ohang yujŏk,” “Tongbukhan ch’ŏngdonggi,” and Chŏpkyŏng ŭi aident’it’i, 123.

20 Kang, “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn,” 435–436.

For the ensuing Bronze Age, the focus remains on the Tumen Basin and southern Maritime Province region while the scope of connectivity tentatively reextends to Gangwon Province. For the Iron Age, the problem of disconnected connectivity reconstitutes between Chungdo Type archaeology in central Korea, and its northern cognates, the Krounovka Culture (southern Maritime Province) and the adjoining Tuanjie Culture in China. While the Tuanjie-Krounovka complex evolves from preceding trajectories of continuity and innovation, Chungdo Type archaeology appears in central Korea without an immediate precursor.

Resolutions through PESCA

Across the periods problematized above, Kang and Kim highlight that the evidence for mid- and long-range connectivity calls for an explanation of material and human movement but that without more systematic analysis, and crucially a framework to enable this, the evidence is left variously unexplored (mid-Neolithic) or neglected (Bronze Age), or where better known, explained through overly simplistic models of ethnic migration (Iron Age).

For the mid-Neolithic, Kim asserts that to propose external northern origins of the burnished redware and raised-line pottery occurring in coastal Korea requires the premise of a “cultural or regional area” (munhwagwŏn ina chiyŏkkwŏn).21 For the early Bronze Age, Kang opines that in order to elaborate exchange between the Korean Peninsula—principally referring to the North Korean sites—and adjacent regions (Mudan Basin and southern Maritime Province), there is a need to discuss the Tumen Basin from the perspective of it being part of a “cultural sphere” (munhwa kwŏn’yŏk).22

21 Kim, “P’yŏngjŏ t’ogi munhwagwŏn,” 9.

22 Kang, “Tuman’gang yuyŏk ch’ŏngdonggi,” 53.

23 Kim, “Hwandonghae munhwagwŏn ŭi yŏksajŏk chomang,” 125.

24 Kang, “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn,” 435. For definitions of the units of analysis, see Kang, “Tongbuk asiajŏk kwanjŏm,” 396–397.

As invoked by Kang and Kim, the rationale for a culture area is thus that it responds to both points of their problematization: material connectivity and disconnected data. Regarding long-range connectivity observed between Gangwon Province and continental regions, PESCA provides a framework enabling explanation of movement within its defined limits through its premise of a common geography and spatial connectedness. It further allows for tracing the changing shape of this connectivity over time.23 Concerning disconnected data, the idea of a culture area functions as a macro-scaled unit of analysis (culture area > culture > assemblage / type > site) enabling South Korean scholars to integrate the varied transnational data in order to model the phenomenon of eastern archaeology as a single complex.24 What then, is PESCA, and how does it work?

Kang and Kim’s invocation of the culture area framework distinguishes PESCA from other areal focused discourses present in South Korean archaeology. However, only Kang has elaborated theoretical understanding of the term. Kang defines a culture area as delineating a region of mutual cultural exchange that effects the spread of a given technology or material innovation, such as agriculture, pottery, dwelling types, or metallurgy.25 In this aspect he notes the culture area to be similar to the concept of an “interaction sphere” (sangho chak’yonggwŏn) with both terms denoting networks of sustained exchange between groups. However, while the latter describes interaction between distinct groups and across regions with potentially differing ecologies and subsistence patterns, the culture area is predicated on a common environment with constituent groups sharing a closer, even “partially genetic relationship.”26

25 Kang, “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn,” 436.

26 Kang, “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn,” 432. In her discussion of figurines, Kim additionally characterizes PESCA as comprising a shared “identity” (aident’it’i) but does not theorize the term further, Kim, Chŏpkyŏng ŭi aident’it’i, 50.

27 Kang, “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn,” 446.

As utilized in Kang and Kim’s writing, PESCA employs two explanatory mechanisms: internal movement and climate change. The shared identity of the vast area that constitutes PESCA is premised on internal material exchange and small group movement. Physical features enabling this movement are the eastern littoral and inland rivers. The latitudinal orientation of the coastline and two major mountain chains (the Changbai-Paektu range in the south, and Sikhote-Alin mountains in the north) are modelled to induce broadly north-south movement with mountain passes and rivers providing lateral connections to the interior.27 Both mountains and rivers play a role in filtering incoming western technological and stylistic influence.

If geography dictates flows of movement, and by extension material connectivity, climate and climate change are posited as the stimulus for developmental trajectories through time.28 Kang and Kim narrate PESCA to emerge in the moderate and relatively stable climate of the mid-Neolithic; in the late Neolithic, c.3000 BCE, temporary cooling coincides with the adoption of intensified mixed-grain agriculture while negatively impacting coastal economies; thereafter the climate stabilizes in the Bronze Age before accelerated cooling coincides with socio-technical developments of the Iron Age. This pattern similarly accounts for the shifting spatial limits of PESCA.

28 Kang and Ko, “Okchŏ munhwa,” 35–37; and Kim, “Hwandonghae munhwagwŏn sŏnsa munhwa.”

29 Kang, “Yŏnhaeju nambu sinsŏkki,” 392.

30 Kang, “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn,” 436; and Kim, Chŏpkyŏng ŭi aident’it’i, 50.

31 Kang, “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn,” 437.

PESCA discourse is characterized by coexistence and interplay of inland and coastal based settlement patterns. Inland sites see the adoption of mixed-grain agriculture and consequently favour alluvial river basins. A coastal economy is evidenced through the archaeology of shell-middens.29 Extracting from later indigenous practice, Kang emphasizes salmon as a core maritime resource, while Kim, through discussion of figurines highlights seal (or sea lion) hunting.30 Despite this inland-coastal dynamic, the integrity of the culture area is preserved through its common isolation from Steppe, China and west Korean peninsular influences.31 The culture area framework models eastern archaeology as its own system. This enables Kang and Kim to narrate internal dynamics of PESCA and its autonomous development through time as central forces that act to mediate and supersede incoming western influence, including in cases such as the innovation and adoption of pottery styles, agriculture, metals and proto-historical peoples.

Etic interlude: origins of PESCA

From an etic perspective, we can note the PESCA framework to be constituted from three elements: 1) the work of Ōnuki Shizuo, 2) North American “culture areas” as defined by Sharer and Ashmore (1987),32 and 3) the Three Age System as an established convention of South Korean archaeology.

32 Sharer and Asmore, Archaeology, 497.

33 Ōnuki, Tōhoku, 46.

34 Ōnuki, Tōhoku, 44.

35 Ōnuki, Tōhoku, 45.

36 Ōnuki, Tōhoku, 91.

Ōnuki’s work treats the same data as subsequently utilized in PESCA, as was available up to the 1990s, but situates it in a broader spatial scope encompassing the Liao River basin in the west to Sakhalin Island in the east (Ōnuki 1998:46).33 For the Neolithic period, Ōnuki defines this larger region as a “far east flat-bottomed earthenware” 極東平底土器 zone characterized by settled gatherer subsistence patterns, and semi-subterranean dwellings entered through the roof. This zone he distinguishes both from Siberia, conversely characterized by tapering earthenware and mobile subsistence patterns, and China.34 Ōnuki periodizes the duration of the zone into two halves. For the first half he delineates three subzones, the easternmost of which comprises the Lower Amur River system to the north, and the Maritime Province connecting to the Tumen basin in the south.35 In the second half the Lower Amur and southern region separate into two less connected regions.36 The spatial scope of the Korean PESCA discourse similarly begins with the same easternmost of Ōnuki’s three zones for the first half of the same periodization but for the latter half it narrows to the southern sub-zone encompassing the southern Maritime Province and Tumen basin.

Ōnuki dates the end of the flat-bottomed earthenware zone to c.2000 BCE.37 In the north, known sites disappear from across the Lower Amur for which Ōnuki posits climatic cooling as a cause.38 Hereon through to the emergence of first generation states, Ōnuki treats the southern Maritime Province, and the adjacent Tumen and Mudan basins—the PESCA core—as their own sub-region distinct in material identity from the Liao and Song river basins to the west, as well as from the north.39 Across this sub-region, Ōnuki synthesizes the archaeological data separately produced in North Korea, Russia and China establishing the methodology adopted for PESCA. In parallel with the other regions, Ōnuki traces the trajectory of this region centered on the Tumen basin to the emergence of Okchŏ40 and thereafter to the Mohe people. Elaborated further below, PESCA discourse follows this same spatial delineation and trajectory to Okchŏ and Mohe groups.

37 Ōnuki, Tōhoku, 116.

38 Ōnuki, Tōhoku, 118.

39 Ōnuki, Tōhoku, 138, 164.

40 Ōnuki, Tōhoku, 183.

41 Sharer and Asmore, Archaeology, 502.

PESCA discourse combines Ōnuki’s synthesizing approach with the “culture area” framework adopted from North American archaeological practice. As a narrative through time, PESCA discourse constitutes a “cultural historical synthesis”—a diachronic tracing of “archaeological variables and their changes through time”—as elaborated by Sharer and Ashmore (1987).41 We should note that the cultural historical synthesis is distinct from European “culture-historical archaeology,” that is often critiqued for conflating material cultures with ethnic groups.

In contrast both to North American culture areas and Ōnuki’s work, PESCA discourse employs the Three-Age System (stone/lithic ages—in this case the Neolithic— the Bronze and Iron ages) as a basic periodization.42 A key subtext to the application of the Three-Age System is that colonial Japanese and Soviet scholarship denied Korea and the Russian Far East distinct or autonomous Bronze and Iron Age periods. For Korean archaeology the elucidation of material and social developments commensurate to the metal age divisions—largely using pottery as the index—has been an important task for decolonizing Korean and east Manchurian late prehistory. As the Three-Age system is now conventional to South Korean archaeology, in the context of PESCA it functions as the organizing principle through which to incorporating transnational data into South Korean archaeological understanding.

42 Ōnuki initially referred to flat-bottomed earthenware as “Neolithic” and notes its duration to align with this period. However, he subsequently eschews Three Age periodization on the grounds that to use Neolithic requires there to be subsequent Bronze and Iron ages but evidence particularly for a Bronze Age is lacking from the northern and easternmost subzones. See Ōnuki, “Tomankō,” 47.

Situating PESCA in South Korea

In this section we consider the significance of PESCA from the viewpoint of South Korea, the country in which PESCA has arisen as a discourse. In this and the following section, I elaborate three topical points of significance: (1) eastern archaeology in South Korea; (2) inaccessibility of eastern North Korea; and (3) the problem of eastern peoples in early Korean history.

First, PESCA provides a framework through which to better account for eastern archaeology occurring within South Korea but that is disconnected from more dominant west-centric trajectories of prehistory and subsequent historical development on the peninsula. As this is a central significance of PESCA let us devote some space to elaborate. The archaeology constituent to PESCA within South Korea occurs principally in Gangwon Province, that occupies the central east of the peninsula. In an article presented at a conference specifically on Gangwon heritage, Kang and coauthor Ko Yŏngmi, begin by alluding to this problem: “Gangwon Province has long been marginalized in [South Korean] archaeological analysis. Rather than a center of civilization, the image of a cold and hazardous borderland region has been stronger, while the basic framework for analyzing [South Korean] sites and artifacts remains beholden to a Three Kingdoms [Koguryŏ, Paekche, Silla]-centrism.”43

43 Kang and Ko, “Okchŏ munhwa,” 33.

While Kang and Ko here refer to the early historical period, Gangwon Province’s isolation extends to prehistory and ultimately owes to geography. The mountainous topography and harsh climate of this region ensure that the east has remained remote from larger population centers that have arisen and consolidated across the west, and secondarily southeast, of the peninsula. This is true both for the full peninsula and its history up to the 1945 division, and for the part of Gangwon today situated in South Korea. In developmental terms, the west has had a twofold advantage in its geography relative to the central and northern east: (1) multiple long west-flowing river basins providing fertile plains supporting larger settlement and popular growth, and (2) proximity to Liaodong (as a meeting point of Eurasian Steppe and northern China cultures) and Central Plain China, both via land and sea routes, that has enabled faster adoption of continental technologies and ideas. As a consequence, a greater volume of prehistoric archaeology occurs in the west, both because there is more to be found and because greater intensity of modern urban development has led to more of its discovery. The west further exhibits material and historical trajectories to the early Three Kingdoms Period states of Korean history, thereafter continuing through the Koryŏ (918–1392) and Chosŏn dynasties (1392–1910), to the capitals and urban conurbations of the modern day peninsula. By contrast, the east has only a narrow littoral between the mountains and sea limiting settlement and population growth. Mountainous topography and climate make it remote at once to the political centers of western Korea and, in turn, to continental regions of China and the Steppe beyond.

The remoteness of the east and its peripherality to west-centered trajectories is at once reflected and further compounded by historiography (the writing of history). The polities of the west and southeast were the dominant forces and wrote histories from their perspective that have become Korea’s historical tradition. In these histories, the extant compilations being the Samguk sagi (1145) and Samguk yusa (c.1280), the peoples of the east are effectively othered and described in a disjointed fashion. They are recorded variously as having constituted minor polities, such as (East) Ye and Okchŏ, that are early on subjugated by expanding west and southeast centered Three-Kingdoms period states of Koguryŏ, Paekche and Silla, and thereafter and in greater predominance as non-state groups, including the Ye, Maek and peninsular Malgal (discussed further below).

Despite the two problems of remoteness and historiographical underrepresentation, Gangwon Province is nevertheless a fully constituent part of (South) Korea, both historically and today. South Korean scholars maintain an active interest in its pre- and proto-historic archaeology understanding it as an integral part of Korea’s heritage. If they could detail more of its early past, they would. To the extent that this archaeology is neglected, it is at once because of the greater volume of data for other regions but more fundamentally because it appears disconnected in three main ways. (1) For the prehistoric periods, the archaeology seemingly occurs in discontinuous waves without developmental continuity between them. For example, initially there are the mid-Neolithic pottery types (impressed patterned pottery, raised-line and redware) such as occur at Osalli; in the Bronze Age these disappear before earthenware connecting in form to west Korean pottery types occurs instead; however, with the transition to the Iron Age there then appears Chungdo Type pottery that is again distinct. (2) None of the prehistoric eastern pottery types or their broader material contexts show connection or convergence with archaeology of the peninsular west. Although the distribution of Chungdo Type pottery extends significantly west, it has been regarded as distinct from west-centered material trajectories.44 (3) Late prehistoric eastern archaeology is disconnected from subsequent trajectories of state formation in the early historical period. While late prehistoric archaeology of western and southeastern Korea anticipates the emergence of first-generation (Three Kingdoms) states, Chungdo Type becomes associated with non-state peoples of the Gangwon Province region.

44 Blackmore, “Critical Examination.”

As a consequence of this disconnection there has been a limit to the significance that South Korean archaeologists can accord eastern archaeology. Against this context, PESCA provides significance by offering a model of connectivity. According to PESCA, what appears in Gangwon Province as isolated and disconnected cultures are oscillations of internal PESCA dynamics; the material trajectories to which they pertain are out of sight of South Korea, but are more continuous in the PESCA core of the Tumen region.

The second significance of PESCA to South Korean archaeology demonstrated in Kang and Kim’s work is that it helps compensate for the inaccessibility and consequent blank of eastern North Korea. It does this principally in the two ways that have been discussed already above, through: (1) reexamining data produced in North Korea, and (2) incorporating data of adjacent regions in China and Russia. A third significance, and a larger topic to which we will now turn, is that later periods of PESCA corresponding to proto- and early history provide coherence and a common identity to the minor and non-state eastern peoples who are underrepresented and denied agency in orthodox Korean history.

Part 2: PESCA at the transition to history

The problem of eastern peoples

As in the case of eastern archaeology, the question of proto-historical eastern peoples, when viewed from the perspective of South Korean scholarship has two scales of concern: (1) regions falling within South Korea, namely Gangwon Province, and (2) the full Korean Peninsula inclusive of current day North Korea, and southern Manchuria. A difference is that while investigation of archaeology has in practice been restricted to South Korea, the discipline of early history, being based on the study of written sources, has continued to treat the fuller spatial scope of eastern Korea and southern Manchuria.

Early peoples within South Korea: Ye, Yemaek and Malgal. For Gangwon Province, the non-state peoples described in sources include groups referred to as Ye or Yemaek, and separately Malgal. The Ye are first attested in Chinese sources from the first century BCE onwards. The Dongyi treatises of the Chinese history, Sanguozhi (third century CE), contains a section on the Ye that locates them on the central east of the peninsula. The historicity of the Ye as a locally used designator has been confirmed through a seal discovered with “Ye Lord” inscribed. “Ye,” however, also occurs in the compound form Yemaek that has been used in both Chinese and Korean sources as a vaguer designation for peoples of the central and northwestern regions of the peninsula. A conventional understanding that has emerged in modern scholarship is that: (1) Yemaek is a general ethnonym for peoples of northern Korea, contrasting with the Han of southern Korea; and (2) those that formed states became known by the polity names (Old Chosŏn, Puyŏ, and Koguryŏ), while the peripheral non-state peoples remained labelled as Ye and Yemaek. Generally the Ye remain associated with the east coast region, while the Yemaek are located more centrally. As a consequence the Samguk sagi records the early Three Kingdoms polities subjugating Yemaek peoples as they consolidate and expand. Paekche, that arose on the Han basin, modern Seoul, battled Yemaek peoples to its north and northeast, that would partially correspond to Gangwon Province (Blackmore 2019:101).45 A later tradition distinguished the Ye of the eastern side of the Taebaek mountains with the supposed Maek of the western side. During the Chosŏn dynasty period (1392-1910) this idea became reified with the region of Gangneung (eastern Gangwon) being associated with Ye, and Chuncheon (western Gangwon) with Maek. This tradition has informed regional identity and popular heritage discourse in Gangwon Province today. The broader point is that in mainstream history Gangwon is associated with Ye and Yemaek from early centuries CE. This association notably overlaps with the distribution and date of Chungdo Type archaeology. During the Three Kingdoms Period, the Gangwon region was partially occupied by Koguryŏ, Paekche and Silla but for each it remained a frontier region so the association of Gangwon with Yemaek pertains throughout the Three Kingdoms Period until post-expansion Unified Silla (668–936) brought the region under fuller administrative integration.

45 Blackmore, “Critical Examination,” 101.

46 Kang, “Malgal charyo,” 156. This Chungdo is the same site as occurs in the name of the earlier dating Chungdo Type culture.

Aside from Yemaek, Korean sources (Samguk sagi and Samguk yusa) also refer to non-state peoples of the central and northern east of the peninsula as Malgal (Ch. Mohe). Mohe is an ethnonym originally designating peoples of far eastern Manchuria—Jilin and the Maritime Province—used from around the late Jin period (266–420) and during the Tang dynasty. They are understood as descendents of the earlier Yilou people, discussed below. In Samguk sagi, the usage of Malgal occurs in entries dating both contemporary to the historical Mohe, but also to earlier centuries. Critical scholars therefore interpret the Malgal in Samguk sagi to reflect two usages: (1) for later centuries it may denote actual Mohe tribes of the northeast Tumen region who were employed by Koguryŏ in its peninsular wars against Paekche and Silla, (2) for earlier centuries it is understood to be an alternative label for non-state peninsular groups of central Korea used interchangeably with Yemaek. The fact of historical Mohe/Malgal on the peninsula in later centuries may have encouraged the anachronistic usage of Malgal for the earlier entries. However, recent excavations at Chungdo, western Gangwon, have uncovered pottery and grave types resembling fifth to sixth-century Mohe archaeology of eastern Manchuria.46

Early peoples of the northeast: Okchŏ and Yilou. Beyond the limits of South Korea, two further entities are associated with the northeast. Okchŏ is attested in name from the late second century BCE as a people occupying the narrow northeastern coast of the peninsula north of the Ye. Sanguozhi distinguishes “southern” and “northern” Okchŏ. Southern Okchŏ was located fully on the peninsula, being first incorporated into the eastern section of the Han dynasty commanderies 109 BCE, and later subjugated by Koguryŏ. Sanguozhi records Southern Okchŏ being laid waste by the Chinese Wei armies in a 245 CE campaign against Koguryŏ. Northern Okchŏ is usually located in the lower Tumen region, but it is unclear how far north or east into the Maritime Province it continued. It is associated with the region in which Koguryŏ would establish its easternmost outpost, Ch’aeksŏng fortress, following its fourth-century expansion. The Yilou (K. Ŭmnu), meanwhile, are attested in Sanguozhi as located north of Northern Okchŏ. They are recorded as having been belligerent to Northern Okchŏ conducting raids by boat against them in the summertime.47 Later Chinese histories identify the Yilou as ancestral to the Mohe who, in turn, were ancestral to the Jurchen.48 By the fifth century, the presumed region of Koguryŏ’s Ch’aeksŏng fortress was largely occupied by Mohe (recorded as Wuji) groups. It seems that Northern Okchŏ was unable to recover from the earlier Wei campaign (that also passed through Northern Okchŏ), and that Yilou (future Mohe) subsequently expanded south into its former territory.

47 These are usually assumed to have been coastal raids, but Kang argues them to have been inland riverine raids.

48 Two intermediary ethnonyms are Sushen 肅愼 and Wuji 勿吉. Byington, Ancient State, 36, 249.

All these minor and non-state eastern peoples—Ye(maek), Okchŏ, Yilou, and Mohe/Malgal—are thus separately named and appear variously disparate from one another, or muddled within the sources. Notably, however, their recorded loci collectively map onto the spatial distribution of eastern archaeology, that from the South Korean perspective appears disconnected but that through PESCA can be understood to have its own coherency. The third significance of PESCA to South Korea, then, is to transpose this coherency onto historical interpretation of the eastern peoples.

Connecting eastern peoples to archaeology

The Ye(maek) peoples have been associated with the Chungdo Type archaeology while Northern Okchŏ has been equated with the Tuanjie and Krounovka cultures of Jilin and the southern Maritime provinces, respectively. These equations of material culture to named entities have been present in interpretations of eastern archaeology prior to and beyond PESCA discourse. Both Chinese and Russia scholars, for example have treated Tuanjie-Krounovka as corresponding to Okchŏ. Thus, from the outset of PESCA, the correspondence of Chungdo Type and Tuanjie-Krounovka archaeology to named peoples was thus a known premise and point of interest. The problem is that such correlations are overly reductionist. Early on, No Hyŏkchin drew attention to this problem cautioning that in cases where sources and material data are insufficient to allow for the matching of named entities with archaeological cultures, one should not be substituted for the other.49 He highlights the paradox that, if the Krounovka culture corresponds to Okchŏ but is materially the same as Chungdo Type archaeology, then how can the peoples of Gangwon Province—named as Ye(maek)—be separately defined or distinguished? No’s solution is to foreground the archaeology, and to the extent that the archaeology constitutes a single complex (Eastern Road / PESCA), he asserts that the groups should be treated as a single people (chongjok).

49 No, “Tongno (East Road),” 35.

Hereafter, it is, again, Kang, who has contributed most to addressing the relationship between the named eastern groups and archaeology. Kang elaborates the internal dynamics of this single people. For the Iron Age and transition to early history he foregrounds two problems: (1) the spread of Tuanjie-Krounovka culture, and (2) the question of the Mohe (K. Malgal). We will see that he resolves these through application of the culture area framework.

Tuanjie-Krounovka and Poltze cultures. The Tuanjie-Krounovka culture first arose on inland river basins. Relative to preceding archaeology, it is characterized by intensification of mixed-grain agriculture enabled through the adoption of iron tools and consequent growth in the size and number of settlements. The culture is additionally characterized by three innovations: hardened pottery; an entrance section on semi-subterranean dwellings presumed to insulate against the cold50; and quasi-hypocaust tunnel hearths constructed within. Kang reasons that these latter features were developed in what proved to be a successful response to climatic cooling, that occurred from the 4th century BCE onwards.

50 Causing the plans to be described as ch’ŏl 凸 or yŏ 呂 shaped.

We can synthesize Kang’s problematization as follows. The Tuanjie-Krounovka culture disappears from the Tuman-southern Maritime Province region around the time that Chungdo Type archaeology appears in central Korea, a period that coincides with climatic cooling. In the Tuman-southern Maritime Province region, meanwhile, Tuanjie-Krounovka culture is understood to have been displaced by the southward spread of the Poltze culture to its north. As a consequence, researchers have typically premised climate change as the primary cause for a chain of presumed southward migrations; according to this scheme, the peoples of the Poltze culture displace the Tuanjie-Krounovka culture, whose peoples migrate south to constitute Okchŏ and Ye. However, this model, Kang argues, is overly simplistic. It has overlooked archaeology of the far north, occurring in the Sanjiang Plain region of the Lower Amur, that is materially similar to Tuanjie-Krounovka and appears at a similar time to Chungdo Type. This indicates that at the same time as the Tuanjie-Krounovka culture spread south, it also expanded north, via the inland Mudan Basin, to the Lower Amur. The fact of this northward spread consequently undermines the idea of climatic cooling having been the sole cause for the southward spread of Tuanjie-Krounovka into the central peninsula.

Consequently, rather than the people of the Tuanjie-Krounovka culture being passive victims forced south in a chain of climate induced migrations, Kang argues the culture to have expanded both north and south owing to it having evolved attributes best adapted to sustain itself—even thrive—within a wider cooling climate.51 The simultaneous spread of the Tuanjie-Krounovka culture to the Han river basin of western Gangwon Province, and to the Lower Amur basin of the far north is because these two basins provided equivalent environmental conditions to the Tuman-southern Maritime Province region, namely, rich alluvial soils supporting mixed-grain agriculture. Climate change was thus a contextual cause for the spread of Tuanjie-Krounovka culture both north and south rather than a singular catastrophe displacing peoples southwards. In contrast to wholesale migration, Kang models the spread of Tuanjie-Krounovka elements north and south as having involved small scale migrations and adoption by local inhabitants as a strategy to thrive in the face of deteriorating climate.52 Kang’s problematization of the spread of Tuanjie-Krounovka culture, and the explanatory model through which he resolves it utilize PESCA framework.

51 Kang, “Tong’asia kogohak,” 70.

52 Kang, “Yŏnhaeju ch’ogi ch’ŏlgi,” 547–548.

53 Kang, “Tong’asia kogohak,” 45–46.

54 Kang and Ko, “Okchŏ munhwa,” 41. This contrasts to Kang, “Kogo charyo,” 58, that deemphasizes the Tuanjie-Krounovka element.

55 Kang and Ko, “Okchŏ munhwa,” 45. Doing so gives privileges the name of Okchŏ over Yilou, thus supporting the name of the “Okchŏ culture area”.

Poltze and Olga cultures. The Poltze culture first arose on the Lower Amur River region before spreading south via the Ussuri River. Dwellings are semi-subterranean, deeper than Tuanjie-Krounovka dwellings, with an entrance through the roof, and without hypocaust hearths. Similar to Tuanjie-Krounovka, the people practiced agriculture along rivers and lakes. However, many settlements exhibit evidence of having been destroyed by fire, while assemblages include armour and iron weapons that are absent from Tuanjie-Krounovka culture.53 Researchers have previously understood the appearance of the Poltze culture in the southern Maritime Province region, there constituting the Olga culture, to have caused the Tuanjie-Krounovka culture to have shifted its locus to northeastern Korea. Under this spatial configuration they have matched the Tuanjie-Krounovka (northeastern Korea) and Poltze (Tumen-southern Maritime Province) cultures to the Okchŏ and Yilou peoples, respectively. Kang challanges this model as overly simplified by highlighting that although the Poltze culture spread south into the Tumen–southern Maritime Province region during the first centuries BCE–CE, rather than fully replacing the Tuanjie-Krounovka culture, there was an extended period of coexistence. More recently Kang has further deemphasized the idea of the Poltze culture having fully replaced Tuanjie-Krounovka culture, instead characterizing the Olga culture as having constituted a hybrid between the two (Kang and Ko 2019:41).54 In this configuration, Kang equates the Olga culture—previously viewed as corresponding to Yilou—to Northern Okchŏ55 (Kang and Ko 2019:45). This is possible through the premise of both belonging to a commom culture area. By suggesting a closer relationship between the two cultures, this interpretation functions to de-reify the traditional Okchŏ-Yilou dichotomy and has implications for Kang’s second topical focus, the question of the Mohe.

The question of the Mohe. Kang’s overarching problematization of the Mohe is as follows. There are clear cases in which the Mohe have been active agents on the Korean peninsula and adjacent regions of the northeast, and there is Mohe-type archaeology associable with them. However, the Korean perception of Mohe history and archaeology at once suffers the same problems of remoteness and disconnection as for other eastern peoples and archaeology, such as Okchŏ or Ye(maek), but the problem is exacerbated because orthodox Korean historiography has viewed the Mohe not just as a non-state other within Korean history, but as a non-“Korean” element, i.e. as a group external to Korean history and identity. As long as the Mohe are viewed as non-Korean, it is difficult to account for their role in Korean history and archaeology.

Kang highlights two examples in which Mohe archaeology is better attested than Koguryŏ. First is the case of Koguryŏ’s Ch’aeksŏng fortress, recorded as having been Koguryŏ’s easternmost outpost and understood to have been located in the lower Tumen region. The problem is that despite continued investigation and excavations in the Hunchun (eastern Jilin) and southern Maritime Province regions, no archaeology associable with Koguryŏ sites occurs; rather, there occurs earlier Northern Okchŏ (Olga culture) archaeology followed by Mohe archaeology.56 If the Mohe are regarded as non-Korean, then in terms of national history, this undermines the northeast being a part of Korea’s early past by way of Koguryŏ. Second is the question of Koguryŏ’s recorded southern expansion into the central peninsula. The archaeological footprint for Koguryŏ in Central Region Korea remains limited, while Mohe archaeology also occurs, such as at Chungdo.57

56 Kang, “Kogo charyo,” 44, “Malgal charyo,” 154; and Kang and Ko, “Okchŏ munhwa,” 43.

57 Kang, “Malgal charyo,” 150, 156–157.

Alluded to by Kang, one of the reasons for viewing the Mohe as non-“Korean”—not a part of Korean history proper—is their position in a genealogy of peoples that has been reified as both ethnically and politically non-Korean. In this linear projection, the Mohe are situated as ancestral to the later Jurchen and Manchu who, having founded dynasties associated with Chinese and Manchurian history, have from the viewpoint of Korean history been viewed as outside of Korean history. Preceding the Mohe, this genealogy begins with the proto-historical Yilou. While the Mohe have been treated as a non-Korean other but attested within Korean history—through their entanglements with Koguryŏ and references to peninsular Malgal—the earlier Yilou, having been beyond the reach of “Korean” states, have not been treated as a part of Korean history at all. That the Yilou are absent from transmitted Korean history reinforces current day presumption of their non-Koreanness. This presumed “non-Koreanness” has been reified in the Okchŏ-Yilou dichotomy as projected onto eastern archaeology, treating the Tuanjie-Krounovka culture as Okchŏ and the Poltze culture as Yilou. These reifications of historiography and archaeology that treat Yilou as non-Korean, circularly reinforce the ambiguity of the Mohe, as the Mohe are seen to be both preceded and followed by non-Korean entities, the Yilou and Jurchen, respectively.

Kang’s answer to the problem—the reification of Yilou and Mohe as non-Korean—is twofold. First, as seen above, Kang dereifies the Okchŏ-Yilou dichotomy as projected onto archaeology by interpreting the Olga (Poltze) culture as itself having formed over the Tuanjie-Krounovka culture, and corresponding to Northern Okchŏ rather than Yilou. He then argues that the specific Mohe groups who arose in the Tumen basin area, known as the Baishan Mohe (K. Paeksan Malgal), were descendents of the people of the Olga culture, that were themselves a hybrid of Okchŏ and Yilou elements. In effect, Kang replaces the non-“Korean” genealogy (Yilou → Mohe) for a hybrid genealogy (Northern Okchŏ → Baishan Mohe). Here we can note that historiographical association of Okchŏ functions to signify “Koreanness” that is then bequeathed to Baishan Mohe independent to the question of evidence for Koguryŏ’s control of the region.

Second, Kang further dereifies both the “Okchŏ-Yilou dichotomy” and the “Yilou-Mohe genealogy” by situating them in the larger common context of PESCA. In his earlier work Kang (2008) distinguishes “Okchŏ” and “Yilou” culture areas, yet highlights that the respective preceding cultures from which they developed—the Uril and Yankovsky cultures—shared closer material similarity than the subsequent Tuanjie-Krounovka and Potze cultures, thus implying the distinction of Okchŏ and Yilou to have been the result of divergence rather than absolute difference.58 More recently (2022) he has emphasized commonality between Okchŏ and subsequent Mohe, stating, “In actuality the Mohe and Okchŏ cultures were not groups of entirely separate genealogies. The difference [between them] emerged through their differing subsistence strategies according to geographical environments within the Pan-East Sea region.”59 In this way he alludes to their shared PESCA context.

58 Kang, “Tong’asia kogohak,” 65.

59 “실제로 말갈계의 문화는 옥저계의 문화와 아예 계통을 달리하는 다른 집단이 아니다. 그들은 환동해 지역에서 지리적 환경에 따라 생계 전략을 달리하는 과정에서 생긴 문화차이이다.” Kang, “Malgal charyo,” 154. See also Kang and Ko, “Okchŏ munhwa,” 46.

60 Kang, “Malgal charyo,” 159.

61 Kang, “Malgal charyo,” 157.

62 Kang, “Malgal charyo,” 159.

Finally, PESCA context also contributes to Kang’s interpretation of Mohe (Malgal) archaeology that occurs in central Korea. Here two problems pertain: (1) the question of the peninsular Malgal attested in Samguk sagi, and (2) the fact of actual Mohe archaeology occurring across Gangwon Province and west along the Han River basin into current day eastern Seoul. Based on the evidence for a weak Koguryŏ presence in the Ch’aeksŏng region, Kang characterizes the Baishan Mohe (Paeksan Malgal) as having themselves been a long “Koguryŏ-ized” yet autonomous component of eastern Koguryŏ that, while politically constituent to Koguryŏ, maintained a Malgal identity.60 He then reasons that they were mobilized or otherwise participated in Koguryŏ’s late-fifth-century southward expansion into central Korea because they were best adapted to the geography of the Gangwon region.61 Based on material differences in the peninsular Malgal archaeology, Kang traces two points of origin: Tumen Basin groups traveling via the east coast, and more northern groups of the Songhua Basin and Lake Khanka regions being represented by distinct Mohe graves and pottery recently uncovered at the Chungdo Legoland site.62 Kang suggests the former to have localized across Gangwon, while the latter were a new Mohe group. In both cases, the routes they travelled, and their adaptability to the environment of Gangwon and the Han basin are two facets explained by the PESCA framework, and echo the earlier material connectivity between Tuanjie-Krounovka and Chungdo Type archaeology.

Part 3: Etic significance and functions of PESCA

We will now consider functions and significance of PESCA discourse viewed from an etic perspective. Here we can first distinguish some of the functions between modalities of archaeology and historiography. We will finish by considering those that derive and apply to the PESCA discourse in its totality, bridging both archaeology and historiography. Across these foci, we can also distinguish functions and significance as they apply to two perspectives: South Korea, and a wider global past (international) perspective.

As archaeology. PESCA discourse is universally significant for providing the most complete synthesis of transnational data for the geographical regions of eastern central and northeast Korea, and eastern Manchuria in any language to date. Its synthesizing methodology builds on the work of Ōnuki. PESCA, however, is distinguished both from Ōnuki and other syntheses, such as Aikens et al. (2009) by going beyond descriptive enumeration of the data.63 While Ōnuki delimits a similar spatial configuration to PESCA, and Aikens et al. invoke the concept of a “cultural zone” as their starting premise, at the discursive level of their writing these principally function as outline frameworks. By contrast, Kang and Kim not only elaborate their framework in greater systematic detail, but actively employ the culture area framework as an explanatory mechanism. Consequently, PESCA functions not merely as an organizing premise for descriptive synthesis, but is itself a central argument that is continuously invoked and substantiated throughout production of the discourse.

63 Aikens, Zhushchikhovskaya, and Rhee, “Environment, ecology.”

By interfacing South Korean archaeology with data of eastern Manchuria, meanwhile, PESCA equally functions to situate eastern South Korean archaeology in broader northeast Asian regional context. From a South Korean perspective, PESCA provides not only a transnational synthesis on South Korean terms—through it being authored by South Korean scholars—but transnationalizes a part of South Korean archaeology. In so doing PESCA contributes to decoupling Korean archaeological interpretation from modern (presentist) concerns of national identity. This is reflective of moves within Korean archaeology towards situating Korea in wider regional perspective.

As historiography. PESCA discourse notably increases the significance of Okchŏ as a proto-historical entity. It does so by maintaining Okchŏ’s association as a part of “Korean” history while according it an autonomous east-rooted aspect. Orthodox historiography associates Okchŏ as “Korean” in part through its association with the northeast of the peninsula, but principally through understanding of it having been subordinated to the west-centered stated of Koguryŏ. PESCA by contrast identifies Okchŏ with other eastern groups and archaeology including those beyond the conventional scope of Korea’s early past, namely, the Yilou. As a consequence, within the transnational space of PESCA discourse, Okchŏ functions as the clearest signifying label of “Koreanness.” From the perspective of South Korean historiography, and especially when framing PESCA discourse for wider public engagement, it is principally Okchŏ that enables the projection of early Korean identity onto late iron-age archaeology extending northeast beyond the Tumen. This projection is necessary for justifying relevance of PESCA in Korean context and communicating significance to a South Korean readership.

Conclusion: complicating west-centrism, and PESCA as its own space

In its totality, PESCA discourse has two main functions. First, through foregrounding eastern archaeology and peoples, PESCA discourse complicates west-centric biases entrenched within both traditional and modern discourses of the early Korean past. West-centered discourse constitutes an epistemological hegemony that foregrounds the emergence of early states across the west, and secondarily southeast of the Korean peninsula and traces their preceding development and supposed “Yemaek” ethnic origins to the Liaodong and Liaoxi regions of China. Historiographically, western bias is centered on the early polity of Old Chosŏn (trad. 2333–108 BCE), that in both orthodox and current day tradition is viewed as the “first state in Korean history” from which all other “Korean” polities and peoples are understood to derive. In archaeological discourse, the northwest is separately privileged through its linkage to technological trajectories of China and the Eurasian Steppe. The Korean people’s own ethno-material origins, meanwhile, are located in the early Bronze-Age cultures of Liaodong and Liaoxi—interpreted as either prefiguring or constituting Old Chosŏn—while preceding impulses for the Neolithic are similarly sought in the enigmatic Hongshan culture of Liaoxi and its immediate predecessors.

PESCA discourse functions to de-privilege these western biases by evincing a material prehistory of the eastern groups named in sources but treated as a minority other in mainstream orthodox history. In the usage of Okchŏ as a label for a wider complex of eastern archaeology, I submit that Okchŏ’s continued signification of “Koreanness” combined with its newly defined eastern-rooted autonomy and PESCA identity all enable Okchŏ, or what Kang also labels the “Okchŏ culture area,” to function in the discourse as a counterpart to Old Chosŏn. By explaining technological developments—understood to be commensurate with evolving social configurations—as processes of small-scale adoption, local spread and innovation, meanwhile, PESCA discourse distinguishes the east from west-centric trajectories of development; the east is no longer just a periphery to the west but its own cultural area. Through tracing earliest common material connections to the mid-Neolithic, PESCA matches, and thus balances, the deep temporal scope of northwest archaeology.

The second significance of PESCA discourse in its totality is its spatial conceptualization. From a South Korean perspective, PESCA functions to foreground the role of the Tumen River basin in the pre- and early history of the Korean Peninsula. As the only major eastward flowing river on the Korean peninsula, the Tumen has clear significance to the early past of the region, however, its long-standing status as a “borderland and prohibited zone”64 and current day international border has led to the Tumen being viewed in both pre-twentieth-century and current (South) Korean discourses as a frontier rather than its own center. The Tumen has previously been accorded significance within archaeological discourses of Japan, North Korea and Russia on which PESCA builds. In South Korea, it is only with PESCA discourse that the Tumen has received fuller attention, but PESCA then goes further than earlier Japanese, North Korean and Russian discourse in conceptualizing the Tumen not merely as a periphery, but as its own nexus. In PESCA discourse the Tumen functions in two main ways: (1) as part of an integrated region straddling North Korea, eastern Jilin and the Maritime Province (comprised of the Mudan and Suifen-Razdolnaya basins), that from the late-Neolithic onwards functions as the core of PESCA, on which, for example, the Tuanjie-Krounovka culture arises; and (2) as a nodal point through and from which material extensions pass and project.

64 Park, Sovereignty Experiments, 23.

65 Park, Sovereignty Experiments, 172–182.

66 Bohnet, Turning toward Edification, 40.

Foregrounding of the Tumen has significance for current English language scholarship in which the region has also been neglected. Aikens et al. (2009) synthesize eastern archaeology of Russia and South Korea but fully omit corresponding data from China and North Korea and consequently overlook the role of the Tumen. In English language Korean Studies, meanwhile, the Tumen region has only recently received attention by way of Alyssa Park (2019) on settler migration into the southern Maritime Province, and Adam Bohnet (2020) on foreigners in the Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1910), that discusses the Jurchen of the northeast. As a prehistory of the same region, PESCA offers points of longue durée intersection with both. The geography of Korean migration from northern Hamgyŏng Province into the southern Maritime Province (Ussuri) from the 1860s onwards, that saw “cross-border networks” and settlement extend also into Jirin, for example, notably maps onto the same core region of PESCA.65 Although this migration was shaped by modern contingencies, the success of Hamgyŏng natives in settling these regions and opening them to cultivation can be explained by viewing their migrations as following the logic of, in fact, internal movement within a common area and ecology, to which, Kang would argue, the patterns of eastern Korean life were long pre-adapted. In the early Chosŏn period, meanwhile, the route Bohnet describes Jurchen envoys taking to the Chosŏn capital at Seoul, “proceeding down the eastern coast… turning inland at Yangyang,” similarly follows the pattern of connectivity modelled in PESCA between the Tumen region and central Korea, Yangyang being the town in which the Neolithic site of Osalli is located.66 Indeed, ancestry of the later Koreans of Hamgyŏng, including those who migrated north, would have included a component from Jurchen communities that in early Chosŏn resided across both sides of the Tumen; those Jurchen in turn inhabited the same region as the earlier Baishan Mohe and, according to Kang, of Northern Okchŏ before them.

In this way, we can highlight one further significance, namely, that PESCA provides a framework to conceptualize a common eastern people and space. Several aspects of this have already been addressed. We have noted that the identification of eastern groups as a common people sharing a common material prehistory enables the projection of eastern Korean identity onto groups and archaeology that have lain beyond the conventional boundaries of Korea’s early past, whether the Yilou and Mohe or earlier material connectivity extending to the Lower Amur. In this South Korean-centered framing, PESCA essentially bolsters the eastern component of Korea (i.e. giving significance to the eastern archaeology and peoples within Korea). The non-Korean-centered equivalent is to recognise PESCA as its own spatial network (i.e. culture area), inhabited by its own peoples. This PESCA-centered perspective is also present in PESCA discourse as authored by Kang and Kim and is, I contend, its core argument. Within the discourse it is clearest for the earlier periods, particularly the mid-to-late Neolithic, but from the proto-historical period when the discourse addresses the problem of named entities, the PESCA-centered perspective becomes obscured—though never negated—by Korea-centered framings.

A PESCA-centered perspective provides two functions. First, maintained into early history, PESCA space and peoples partially prefigure the later state of Parhae (698–926). In west-centered histories, Parhae is understood as a successor state to Koguryŏ owing to it having been established by remnant groups. However, geographically Parhae had a stronger eastern orientation, being more centered on eastern Jilin (originally the center of Puyŏ), with territory extending into the southern Maritime Province and eastern Korea. Further, while Parhae also possessed a Koguryŏ component, its core population, particularly of the eastern region, was largely comprised of Mohe groups. Its material identity was also distinct from Koguryŏ. Parhae’s eastern capital was located in the lower Tumen (former Ch’aeksŏng).67 Parhae more fully embraced the logic of PESCA than the west-centered state of Koguryŏ before it. This significance can support South Korean claims to Parhae, or it can support a Parhae-centered perspective.

67 Kang has noted that Parhae sites excavated in Russia invariably contain earlier Okchŏ layers (Kang 2020:48).

Second, and more broadly, the PESCA-centered perspective enables a space (or network) and people to be attended to as their own dynamic across pre- and early regional history. Here, we should be conscious of, and go beyond using these concepts of a PESCA space and people only as a challenge to non-PESCA-centered norms, that might derive from presentist interpretations or west-centric perspectives. For example, in according significance to PESCA as its own space, we can highlight most immediately that the concept of PESCA functions to deborder a region that (from our presentist perspective) has previously only been viewed as a frontier to west-centered forces. Here the concern of borders is not limited to modern national borders but extends to pre-twentieth century configurations; it may even trace to the early historical period that overlaps with PESCA—for example, when the Lower Tumen was an eastern frontier of Koguryŏ. However, it is still a longue durée presentist concern, while the greater part of PESCA temporality pertains to the prehistoric period, prior to borders. I argue, a view of PESCA centered on its own temporality and space functions not only to defamiliarize modern and historical era space (longue durée presentist concerns), but does so by evincing—effectively refamiliarizing us with—a “forgotten” actual alternative pattern of the past, that pattern being the PESCA complex.

We have noted, meanwhile, that the notion of a PESCA people provides a common identity for the communities that emerge in sources as disparate, non-state “others.” However, to define PESCA identity only as the sum of these negatives would be to remain hostage to historiographical bias. The PESCA-centered perspective not only de-others these proto-historical peoples but foregrounds the communities constituting PESCA from the mid-Neolithic onwards as autonomous subjects of their own networked space. Their identity need not be ethnic or political, but derives from the “PESCA argument” for common environmental adaptions and shared technologies. PESCA identity is manifest in materiality; to the extent there is material connectivity, there is a networked identity.

Bibliography

Aikens, C. Melvin, Irina S. Zhushchikhovskaya and Song Nai Rhee. “Environment, ecology, and interaction in Japan, Korea and the Russian Far East.” Asian Perspectives 48, no.2 (2009): 207–248.

Blackmore, Hari. “A Critical Examination of Models Regarding a Han 韓 – Ye 濊 Ethnic Division in Proto-Historic Central Korea, and Further Implications.” Asian Perspectives 58, no.1 (2019): 95–122.

Bohnet, Adam. Turning toward Edification: Foreigners in Chosŏn Korea. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2020.

Byington, Mark. The Anceient State of Puyŏ in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center.

Kang, Inuk. “Ch’ŏngdonggi sidae ch’ŏlgi sidae han’guk kwa yŏnhaeju ŭi kyoryu: Hwandonghae munhwagwŏn ŭi chean kwa kwallyŏn hayŏ” [Exchange between Korea and the Maritime Province during the Bronze and Iron Ages: concerning a proposal for a Pan-East Sea Culture Asia]. Pusan kyŏngnam wŏllye palp’yohoe charyojip 75 (2006).

Kang, Inuk. “Tuman’gang yuyŏk ch’ŏngdonggi sidae munhwa ŭi pyŏnch’ŏn kwajŏng e taehayŏ: tongbukhan t’ogi ŭi p’yŏnnyŏn mit chubyŏn chiyŏk kwa ŭi pigyo rŭl chingsim ŭro” [Concerning the process of change in culture in the Tumen River basin during the Bronze Age: focusing on the chronology of earthenware of northeast Korea and comparison with nearby areas]. Han’guk kogohakpo 62 (2007a): 46-89.

Kang, Inuk. “Yŏnhaeju ch’ogi ch’ŏlgi sidae kkŭrounobŭkka munhwa ŭi hwaksan kwa chŏnp’a” [The expansion and diffusion of the Krounovka Culture in the Maritime Province during the Early Iron Age]. Che 13 hoe han’guk kogohak chŏn’guk taehoe (2007b): 529–555.

Kang, Inuk. “Tong’asia kogohak – kodaesa yŏn’gu sok esŏ okchŏ munhwa ŭi wich’i” [The location of Okchŏ culture in the archaeology and early history of Northeast Asia]. In Kogohak ŭro pon okchŏ munhwa, 18–82. Seoul: Tongbuk’a yŏksa chaedan, 2008.

Kang, Inuk. 2009a. “Hwandonghae sŏnsa munhwagwŏn ŭi sŏljŏng kwa pun’gi” [Establishment and periodization of the Pan-East Sea Prehistoric Culture Area]. Tongbuga munhwa yŏn’gu 19 (2009a): 429–450.

Kang, Inuk. “Yŏnhaeju nambu sinsŏkki sidae chaisanop’ŭkka munhwa ŭi yuhyŏng: yuhyŏng pun’gi mit wŏnsi nonggyŏng e taehayŏ” [Zaisanovka Cultural type/assemblage in the southern Maritime Province during the Neolithic: typology, periodization and primitive agriculture]. In Sŏnsa non’gyŏng yŏng’gu ŭi saeroun tonghyang, edited by An Sŭng-mo and Yi Chun-jŏng, 372–415. Seoul: Sahoe p’ŏngnon, 2009b.

Kang, Inuk. “Tongbuk asiajŏk kwanjŏm esŏ pon pukhan ch’ŏngdonggi sidae ŭi hyŏngsŏng kwa chŏn’gae” [Formation and unfolding of the north Korean Bronze Age viewed through a northeast Asian perspective]. Tongbuga yŏksa nonch’ong 33 (2011): 385–436.

Kang, Inuk. “Samgang p’yŏngwŏn kont’oryŏng p’ungnim munhwa ŭi hyŏngsŏng kwa mulgil tumangnu malgal ŭi ch’ulhyŏn” [三江平原 滾兎嶺ㆍ鳳林문화의 형성과 勿吉ㆍ豆莫婁ㆍ靺鞨의 출현] [The formation of the Guntuling and Fenglin cultures on the Sanjiang Plain, and the appearance of the Wuji, Doumolou and Mohe]. Koguryŏ parhae yŏn’gu 52 (2015):107–147.

Kang, Inuk. “Kogo charyo ro pon paeksan malgal kwa koguryŏ ŭi ch’aeksŏng” [Paeksan Malgal (Ch. Baishan Mohe) and Koguryŏ’s Ch’aek-sŏng fortress viewed through archaeological data]. Tongbuga yŏksa nonch’ong 61 (2018): 42–79.

Kang, Inuk. Okchŏ wa ŭmnu: sumgyŏjin uri yŏksa sok ŭi pukpang minjok iyagi [Okchŏ and Ŭmnu: the story of northern people hidden within our/Korean history]. Seoul: Tongbuk’a yŏksa chaedan, 2020.

Kang, Inuk. “Malgal charyo rŭl chungsim ŭro pon sŏgi 5–6 segi hanbando chungbu chiyŏk kwa yŏnhaeju” [The Korean Central Region and the Maritime Province during the fifth to sixth centuries CE viewed through Malgal (Ch. Mohe) materials]. Kogohak 21, no.2 (2022): 143–165. https://doi.org/10.46760/jbgogo.2022.21.2.143.

Kang, Inuk, and Ko Yŏng-mi. “Okchŏ munhwa ŭi hwaksan ŭro pon kangwŏndo chungdosik t’ogi munhwa ŭi chŏngch’esŏng kwa kyoryu.” [The identity and external exchange of Chungdo Type earthenware culture of Gangwon Province viewed as an expansion of Okchŏ culture]. In Che 2 hoe kangwŏn kodae munhwa yŏn’gu simp’ojiŏm: kodae kangwŏn ŭi taeoe kyoryu, 33–55. Kungnip ch’unch’ŏn pangmulgwan, 2019.

Kim, Chaeyun. “Hanbando kangmok t’oldaemun t’ogi ŭi p’yŏnnyŏn kwa kyebo” [Chronology and genealogy of augmented notched-rimmed t’oldaemun earthenware]. MA thesis. Seoul National University, 2003.

Kim, Chaeyun. “Hanbando kangmok t’oldaemun t’ogi ŭi p’yŏnnyŏn kwa kyebo” [韓半島 刻目突帶文土器의 編年과 系譜] [Chronology and genealogy of augmented notched-rimmed t’oldaemun (perforated rimmed) earthenware]. Hanguk kogohakpo 46 (2004): 31–70.